Introduction

Naturtejo UNESCO Global Geopark joined the European and Global Geoparks networks under the auspices of UNESCO, in 2006. It was included in the International Geosciences and Geoparks Programme of UNESCO in 2015 as a territory of 5067 km2, covering the municipalities of Castelo Branco, Idanha-a-Nova, Nisa, Oleiros, Penamacor, Proença-a-Nova, and Vila Velha de Ródão, located in Central Portugal. Represented by deposits from the Neoproterozoic to the Quaternary, the Ordovician successions are among the main features of the Naturtejo geological heritage, exposed in large, kilometers to tens of kilometers long, Variscan-folded structures, forming Appalachian-type landforms and representing some of its most famous geosites (e.g., the Penha Garcia Ichnological Park and the Portas de Ródão Natural Monument).

The Middle Ordovician is the most fossiliferous Ordovician series across the Central Iberian Zone. The so-called “tristani beds” (Born 1916), due to the abundance of the trilobite Neseuretus tristani in these shallow marine deposits, represents the Oretanian-Dobrotivian interval (correlated with most of the global Darriwilian Stage), which hosts the most classical Portuguese Ordovician fossil sites (e.g. Valongo, Arouca and Buçaco; e.g., Romano 1982; Couto et al. 1997; Guy & Lebrun 2010). While in Northern Portugal these stages are represented by a homogeneous succession of shales and siltstones (Valongo and Moncorvo formations) overlying the ‘Armorican Quartzite’ (Santa Justa and Marão formations, Romano & Diggens 1974; Sá et al. 2005), in central Portugal this interval is represented by intercalation of mudstones and sandstones units: Brejo Fundeiro, Monte da Sombadeira, Fonte da Horta, and Cabril formations (Cooper 1980; Young 1988). Among these, the lower Dobrotivian Fonte da Horta Formation is the most fossiliferous unit, providing highly diverse assemblages (mainly brachiopods, trilobites, ostracods, molluscs, hyolithids, bryozoans, and crinoids), with fewer but frequent fossils also reported from the Brejo Fundeiro and the Cabril formations (e.g., Delgado 1908; Young 1985). Finally, the paleontological record of the Monte da Sombadeira Formation is sparse, but documented (e.g., Delgado 1908; Cooper 1980; Romão 2006).

Within the Naturtejo Geopark area, fossiliferous Oretanian and/or Dobrotivian units are represented in four of its five structural Variscan-folded structures: the Fajão-Muradal, the Vila Velha de Ródão, and the Penha Garcia synclines plus the Monforte da Beira folded structure. During the first decades of geological studies in Portugal, the Middle Ordovician of these sectors was considered poorly fossiliferous, bearing solely rare and badly preserved remains, what was interpreted as being related to deeper environments (Delgado 1908). During the second half of the twentieth century, the discovery of Middle Ordovician fossiliferous levels in Fajão-Muradal, Vila Velha de Ródão and Penha Garcia synclines changed somewhat this interpretation (e.g., Thadeu 1951; Ribeiro et al. 1965, 1967; Perdigão 1971; Young 1988), but their paleontological record was rarely figured (e.g., Neto de Carvalho et al. 2014), and the idea of a low potential for this paleontological heritage remains.

In this work, we show this potential through a selection of specimens from old and new fossil sites, improving the Middle Ordovician biostratigraphy of this region and updating the knowledge of its fossil assemblages, which are fairly more diverse than previously considered.

Stratigraphic Settings of Naturtejo Oretanian/Dobrotivian (Darriwilian) Sequences

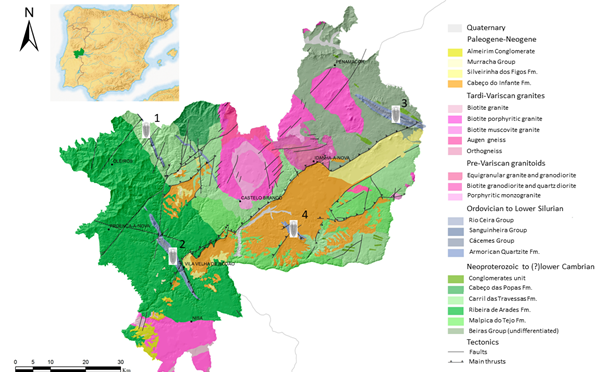

The studied area belongs to the Central Iberian Zone (CIZ) of the Iberian Massif, corresponding to post-Cambrian metasedimentary sequences that lie in angular unconformity on the Beiras Group (upper Ediacaran -?lower Cambrian). Five NNW-SSE to WNW-ESE major Variscan-folded structures, preserving lower Paleozoic successions ranging in age from Lower Ordovician (Tremadocian) up to, at most, lower Silurian (Llandovery), occur within the Geopark: Fajão-Muradal, Vila Velha de Ródão, Penha Garcia, Castelo Branco – Unhais-o-Velho and Monforte da Beira sectors (Fig. 1). Only the southern half of the 32 km-long Fajão-Muradal Syncline lies within Naturtejo area, roughly south of the Zêzere River (Fig. 1). For this reason, herein we will focus only on the Muradal sector when referring to Fajão-Muradal Syncline.

Figure 1. Simplified geological map of the Naturtejo UNESCO Global Geopark (adapted from the 1:500000 map published by Serviços Geológicos de Portugal, Oliveira et al. 1992) with the location of the four sectors indicated in the text: 1 – Fajão-Muradal Syncline; 2 – Vila Velha de Ródão Syncline; 3 – Penha Garcia Syncline; 4 – Monforte da Beira folded structure.

The Oretanian/Dobrotivian (middle to upper Darriwilian) succession among the Naturtejo area starts with the Brejo Fundeiro Formation (20-120 m), conformably overlying the Serra do Brejo and Penha Garcia formations (‘Armorican Quartzite’, Cooper 1980; Bayet-Goll & Neto de Carvalho 2020). This metapelitic unit is recognized throughout all Naturtejo sectors, thickening southwards, from solely 20 m in southern half of the Fajão-Muradal Syncline to 120 m in Vila Velha de Ródão, and eastwards, to about 80 m. The Brejo Fundeiro Formation is assigned to the regional Oretanian stage (middle to upper Darriwilian). In Castelo Branco – Unhais-o-Velho and Monforte da Beira exposures, the lower Paleozoic succession is preserved only up to part of the Brejo Fundeiro Formation, being impossible to estimate its original thickness. A sudden change in lithology marks the base of the following unit, the Monte da Sombadeira Formation (5-50 m), a regressive storm-generated sandstones sequence of lower Dobrotivian age (ca. uppermost Darriwilian). Its thickening and coarsening tendency south and eastwards in Portuguese Central Iberian Zone (Young 1985), is also verified in the studied area, being only 5 m thick in Fajão-Muradal, 20 m in Vila Velha de Ródão and 50 m in the Penha Garcia Syncline. Conformably overlying these micaceous sandstones is the Fonte da Horta Formation (20-65 m), consisting of mudstones with rare sandstone beds, also of lower Dobrotivian age. It was recognized throughout the synclines of Fajão-Muradal, Vila Velha de Ródão and Penha Garcia. The Fonte da Horta Formation rapidly thins southwards, from 55-65 m in Fajão sector (Young 1988; Metodiev et al. 2009) to solely 10-15 m in Muradal and Vila Velha de Ródão areas, thickening eastwards in Penha Garcia to about 50 m. Finally, this mudstone-dominated unit is overlaid by the Cabril Formation, composed of siltstones and sandstones beds exhibiting hummocky cross-stratification within a background of laminated siltstones and mudstones. This unit is assigned to the base of the upper Dobrotivian (global uppermost Darriwilian), being less than 30 m thick and poorly characterized in the Penha Garcia Syncline (Young 1985). In its type area (Buçaco Syncline) and the Amêndoa-Carvoeiro Syncline (located westwards of the studied sequences), the top of the Cabril Formation is marked by a persistent phosphatic conglomerate, not represented in any of the Naturtejo’ sectors. Likewise, the following unit in the Buçaco and Amêndoa-Carvoeiro synclines, the Carregueira Formation, is also absent in the studied sequences. Deposition conditioned by eustatic events and an erosive episode that preceded the deposition of the Upper Ordovician (probably related to the Sardic phase, a deformation event along the northern Gondwana margin; e.g., Puddu et al. 2019) may justify the incompleteness of the Cabril Formation and the absence of the Carregueira Formation in Naturtejo sectors. Furthermore, Young (1988) recognized a maximum shoaling during the deposition of the upper part of the Cabril Formation and concluded that Carregueira Formation, which shows marked thickness variations, may be absent in the “rise” areas. According to the stratigraphic data presented herein, the Fajão-Muradal Syncline marks the belt of maximum condensation of the sequences during the Middle Ordovician. Thus, the sedimentary model suggested by Young (1988) supports and justifies the verified sedimentary hiatus for this sector and south-eastwards areas.

Paleontology and Biostratigraphy

Fajão-Muradal Syncline (southern sector)

The first Middle Ordovician fossils from the Fajão-Muradal Syncline were reported by Thadeu (1951, pp. 38-39), but all the occurrences are from the northern part of the syncline (outside the studied area). Besides graptolites in the Brejo Fundeiro Formation, this author recovered numerous fragments of the trilobite Neseuretus tristani, two indeterminate orthid brachiopods and one ostracod from the mudstones of the Fonte da Horta Formation. Two decades later, Perdigão (1971) presented the only previously reported fossil occurrences from the Middle-to-Upper Ordovician of the Muradal sector. Several fossil sites for the Brejo Fundeiro Formation were documented, yielding the characteristic graptolite Didymograptus (Sarnadas de S. Simão, Picoto, Candal, Zebro and Orvalho). In the Fonte da Horta Formation, Perdigão (1971) identified one single fossil site (Candal at Sarnadas), yielding the trilobite Neseuretus tristani and indeterminate crinoids. One single specimen of a graptolite from the Muradal sector was figured (‘D. bifidus’: Perdigão 1971, pl. 1, fig. 6) and up to now, this was the only Middle Ordovician fossil ever published from there. The recent geologic mapping survey conducted by Metodiev et al. (2010) did not provide fossil remains from the southern sector of the syncline. From a paleontological point of view, the Middle Ordovician of the Muradal region is fairly fossiliferous (Fig. 2), and the present work revealed several new fossil sites, increasing the total number of known species from three to almost 30. The Brejo Fundeiro Formation provided three fossiliferous horizons in the lower part of the unit containing an assemblage representative of the Oretanian age, yielding graptolites (Didymograptus murchisoni and Didymograptus cf. artus), echinoderms (Calix sp.), trilobites (Neseuretus cf. avus and Asaphellus sp.), bivalves (Redonia deshayesi, Praenucula?sp.), brachiopods (Orthidae indet.) and hyolitids (Figs. 2A-E). No fossils were found up to the moment in the Monte da Sombadeira Formation. The mudstones of the Fonte da Horta Formation are very fossiliferous, like in other geographic sectors of central Portugal. Its fossil assemblage is typical of lower Dobrotivian age, yielding abundant trilobites (Neseuretus tristani, Kerfornella brevicaudata, Crozonaspis cf. struvei, Plaesiacomia oehlerti, Isabelinia?sp., Phacopidina micheli, Selenopeltis sp. and Eccoptochile sp.), ostracods (Lardeuxella bussacensis, Reuentalina ribeiriana, Quadritia tromelini, Medianella sp., Quadrijugator marcoi), bivalves (Cardiolaria beirensis), brachiopods (Crozonorthis musculosa, Heterorthina sp.and Horderleyella sp.), indeterminate crinoids and the ichnospecies Tomaculum problematicum. The Cabril Formation did not provide fossils up to the moment.

Figure 2.Fossils from theOretanian (A-E) and Dobrotivian (F-S) of the southern half of the Fajão-Muradal Syncline. A-E, Brejo Fundeiro Formation at Orvalho Village; F-S, Fonte da Horta Formation at Orvalho Village (F,G,J-S) and Sobral do Queixo (Vilar Barroco) locality (H,I). A) The bivalve Redonia deshayesi (internal mold, right valve). B) The trilobite Neseuretus cf. avus (internal mold of a pygidium). C) The trilobite Asaphellus sp. (internal mold of a pygidium). D) The diploporite echinoderm Calix sp. (latex cast of an external mold). E) The lophophorate Hyolithidae indet. (Longitudinal section). F) Trilobites Neseuretus tristani and Phacopidina micheli (the former, yellow color: Internal mold of an exuvium; the latter, white color: internal mold of a cranidium); G, I, J, the trilobite Phacopidina micheli. ((G) Internal mold of a librigenal, preserving the eye surface with lenses. I) Internal mold of a cranidium. J) Internal mold of a pygidium)). H), Tomaculum problematicum (fecal pellets accumulated on sediment surface)). K) The trilobite Kerfornella brevicaudata (internal mold of a cranidium). L) Neseuretus tristani and the bivalve Cardiolaria beirensis (latex cast of an external mold of a pygidium and an articulated specimen, respectively). M) Plaesiacomia oehlerti and Lardeuxella bussacensis (internal mold of a cranidium and an isolated valve, respectively). N) The crustacean ostracod Quadrijugator marcoi (internal mold of a right valve). O) The ostracod Lardeuxella bussacensis (internal molds of several valves). P) Ostracods accumulation (mainly internal molds of Lardeuxella bussacensis and external molds of Quadritia tromelini). Q) Cardiolaria beirensis (internal mold of a left valve). R) The brachiopods Crozonorthis musculosa and Heterorthina sp.(internal molds of ventral – the former, and dorsal – the latter, valves). S) The brachiopod Horderleyella sp. with Quadrijugator marcoi (latex cast of an internal mold of a dorsal valve and internal mold of a left valve, respectively). All scale-bars = 5mm, except G, M, O (= 2 mm) and N (=1 mm). All photographs from the authors.

Vila Velha de Ródão Syncline

The Geological Survey of Portugal had developed some work in the Ordovician sequence of this structure during the second half of the nineteenth century, but Delgado (1908, p. 70) considered its Middle Ordovician units to be sparsely fossiliferous, bearing rare and poorly preserved fossils, which he interpreted as related to deeper sedimentary settings. Nevertheless, there is a good, although poorly diverse, collection recovered by that author, housed in the National Laboratory of Geology and Energy (eight Oretanian/Dobrotivian species) which, together with additional materials collected during the twentieth century, were listed and taxonomically updated by Neto de Carvalho et al. (2009). In a preliminary study, Thadeu (1951) found some fragments of trilobites and brachiopods in the Middle Ordovician mudstones of the Fonte da Horta Formation. Some years later, Ribeiro et al. (1965, 1967) reported Didymograptus, Neseuretus tristani, ‘Dalmanella testudinaria’(probably Horderleyella sp.), ostracods and indeterminate bivalves. Furthermore, they described some levels as bearing abundant fossils, although poorly diverse (e.g., Barroca da Senhora and Quinta da Carga). By the same time, Romariz & Gaspar (1968) published an important graptolite fossil site yielding Didymograptus amplus, a species previously unknown in Portugal but later considered to be a junior synonym of D. murchisoni (Jenkins 1987). Our prospection work corroborates what was previously considered: although bearing highly fossiliferous levels, the Middle Ordovician assemblages of the Vila Velha de Ródão Syncline are poorly diverse and only a few new occurrences are herein reported (including new fossil sites in the vicinities of Perdigão village). Nevertheless, the Brejo Fundeiro Formation hosts good fossil localities, yielding complete and well-preserved specimens with geoheritage potential (Fig. 3A-G), some of them protected as geosites under the Portas de Ródão Natural Monument. On the other hand, it is expected that increasing the prospection works will lead to a higher diversity: the identified taxa correspond to the most abundant species occurring in coeval levels from other CIZ sectors and in those regions many of the less common species were only discovered due to decades of intense fossil collecting (e.g., Buçaco and Amêndoa-Carvoeiro synclines). So far, the Oretanian Brejo Fundeiro Formation provided trilobites (Neseuretus tristani, Ectillaenus giganteus and Eodalmanitina destombesi), pelagic graptolites (Didymograptus murchisoni, Didymograptellus bifidus), bivalves (Redonia deshayesi), brachiopods (Sivorthis noctilio), echinoderms (Calix cf. sedgwicki) and ostracods (Lardeuxella bussacensis), besides the ichnofossil Arachnostega gastrochaenae which usually infests internal molds of trilobites. In the Fonte da Horta Formation, several fossiliferous levels contain Dobrotivian assemblages yielding trilobites (Neseuretus tristani, Colpocoryphe cf. rouaulti and Plaesiacomia oehlerti), ostracods (Lardeuxella bussacensis, Quadrijugator marcoi and Reuentalina sp.), bivalves (Glyptarca sp.) and brachiopods (Heterorthina kerfornei and indeterminate orthids). No fossils were recovered from the Monte da Sombadeira Formation, and only few trilobite remains (Neseuretus tristani) were found in the Cabril Formation.

Figure 3.Fossils from theOretanian (A-D, H) and Dobrotivian (E-G) of the Vila Velha de Ródão Syncline (A-G) and Monforte da Beira folded structure (H). A-D, Brejo Fundeiro Formation at M1373 road; E-G, Fonte da Horta Formation at Barroca da Senhora (E) and Perdigão surroundings (F-G); H, Brejo Fundeiro Formation at NW of Monforte da Beira. A) The pelagic hemichordate graptolite Didymograptus murchisoni (several stipes). B) Neseuretus cf. tristani (internal mold of an exuvium). C) Calix cf. sedgwicki (external mold of plates with detail of tubercles and diplopores). D) Ectillaenus giganteus (internal mold of a complete exoskeleton). E) accumulation of (mainly) Neseuretus tristani sclerites. F) Trilobites Plaesiacomia oehlerti (left) and Neseuretus tristani (right) (internal molds of cranidia). G) Neseuretus tristani (internal mold of a cranidium). H) Ogyginus forteyi (external

mold of a pygidium). All scale-bars = 5 mm. All photographs from the authors.

Penha Garcia Syncline

As for the previous structures, the early decades of geologic studies (Delgado 1908) did not detect paleontologic potential in the Middle Ordovician sequence of the Penha Garcia Syncline. Later, Thadeu (1951) reported the trilobite Neseuretus tristani and two indeterminate brachiopod species, probably from the Dobrotivian Fonte da Horta Formation. A slightly higher, but still low, diversity was reported by Perdigão (1971) who identified one bivalve (Ctenodonta sp.), brachiopods (‘Harknessella cf. vespertilio’ and ‘Orthis’ sp.)and indeterminate crinoids in the Oretanian/Dobrotivian mudstones, figuring only two specimens (Perdigão 1971, pl. 1, figs. 5,7). The important lithostratigraphic work performed by Young (1985) improved the Dobrotivian biostratigraphic knowledge of the Penha Garcia Syncline, documenting the occurrence of the brachiopods Heterorthina kerfornei, H. morgatensis, Crozonorthis musculosa (figured on op. cit., pl. 19, figs. 13,15) and Aegiromena mariana (first occurrence in Portugal, figured on op. cit., pl. 28, figs. 18-19), plus few trilobites (Neseuretus tristani, Prionocheilus mendax, Ectillaenus sp., Colpocoryphe sp.and Placoparia sp.) in Monte da Sombadeira and Fonte da Horta formations. By the end of the last century, the geologic mapping surveys of Sequeira et al. (1999) provided few trilobites (non-identified) in the Brejo Fundeiro Formation. More recently, Neto de Carvalho et al. (2014) presented an update of occurrences and fossil sites in the Middle Ordovician of the Penha Garcia Syncline (e.g., Ribeira do Reca, Fonte do Cuco), including the complete revision of the existing collections from the National Laboratory of Geology and Energy. These authors identified six trilobites, three brachiopods, plus bivalves, crinoids, ostracods, orthocerids andthe ichnofossils Arachnostega gastrochaenae and Planolites montanus. Part of this material is here revised, together with a few new specimens (Fig. 4), demonstrating the potential for future paleontologic works in the Middle Ordovician of the Penha Garcia Syncline, where fossil heritage from both the Lower and Upper Ordovician is also outstanding (Neto de Carvalho et al. 2014). The Brejo Fundeiro Formation yields a typical Oretanian assemblage of trilobites (Neseuretus tristani, Eodalmanitina destombesi, Colpocoryphe cf. rouaulti, Ogyginus sp.), brachiopods (Cacemia cf. ribeiroi, Sivorthis noctilio and Paralenorthis sp.), bivalves (Redonia cf. deshayesi, Hemiprionodonta lusitanica and Praenucula costae), rostroconchs (Tolmachovia sp.), graptolites (Didymograptus murchisoni, D. cf. artus, Didymograptellus bifidus, Hustedograptus cf. teretiusculus, Diplograptus sp.) and indeterminate orthocerids. The Monte da Sombadeira Formation only provided the brachiopod Heterorthina morgatensis in its upper ferruginous beds (Young 1985), an index-species of uppermost Oretanian-lowermost Dobrotivian in Ibero-Armorica (Gutiérrez-Marco et al. 2016). The Fonte da Horta Formation yields a low-diversity assemblage of lower Dobrotivian age, containing trilobites (Neseuretus tristani, Prionocheilus mendax, Placoparia cf. tournemini, Ectillaenus giganteus and Colpocoryphe sp.), brachiopods (Apollonorthis cf. bussacensis, Heterorthina morgatensis, H. kerfornei, Aegiromena mariana and Crozonorthis musculosa), ostracods (Lardeuxella bussacensis and Medianella sp.) and trepostomate bryozoans. The Cabril Formation did not provide fossils up to now.

Figure 4. Fossils from theOretanian (A-J) and Dobrotivian (K-M) of the Penha Garcia Syncline. A-J, Brejo Fundeiro Formation at Fonte do Cuco (A), Serra do Ramiro (B), Barragem (C,D,H), Ribeira do Reca (E,F,I,J) and Arraial da Antónia Tomé (G) localities; K-M, Fonte da Horta Formation at Ribeira da Nave locality. A) Didymograptus murchisoni (one rabdosome). B) The cephalopod nautiloid Orthocerida indet. (Internal mold). C) The trilobite Colpocoryphe cf. rouaulti (internal mold of an exuvium). D) Ogyginus sp. (internal mold of an exuvium). E) Neseuretus tristani (internal mold of a cranidium). F) The brachiopod Paralenorthis sp. (internal mold of a ventral valve). G) The mollusc rostroconch Tolmachovia sp. (internal mold of the right side of the shell). H) Redonia cf. deshayesi (internal mold of a left valve); I, Hemiprionodonta lusitanica (internal mold of a left valve partially preserving the mineralized shell). J, the bivalve Praenucula costae (internal mold of a left valve). K) A brachiopod Orthidae indet. (Internal mold of a valve). L) The trilobite Placoparia cf. tournemini and Orthidae indet. (Internal mold of a complete exoskeleton and external mold of a valve, respectively). M) The brachiopods Apollonorthis cf. bussacensis, Heterorthina sp. and a bryozoan Trepostomata indet. (external and internal, respectively, internal molds of dorsal valves). All scale-bars = 5 mm. All photographs from the authors

Monforte da Beira folded structure

The first and only Oretanian fossil assemblage reported from this complex structure was found by Delgado (1908, p. 71), who reported a pygidium of an asaphid trilobite, orthocerids, a lingulid brachiopod and an indeterminate bivalve, coming from mudstones he assigned to his ‘Schistes à Orthis Ribeiroi’, currently the Brejo Fundeiro Formation. This is the only Ordovician lithostratigraphic unit recognized by us above the ‘Armorican Quartzite’, and the limited exposure area may justify not having been detected in the recent geological map published for this region (Romão et al. 2010). Nevertheless, no additional material was found. Thadeu (1951) also recognized this Oretanian succession of purple micaceous mudstones, but part of his selected sections corresponds to the Neoproterozoic Beiras Group. The revision of Delgado’s (1908) material allowed the identification of the trilobite Ogyginus forteyi (Fig. 3H), characteristic of Oretanian in Iberia and thus confirming the representation of this stage in the Monforte da Beira structure.

Geoconservation and Geotourism Potential

Most of the fossil sites from the Middle Ordovician are included in the Inventory of Geological and Geomining Heritage of the Naturtejo UNESCO Global Geopark. At Fajão-Muradal Sycline, the Orvalho roadcut section was recognized as geosite in the Master Plan of the Municipality of Oleiros. It is also associated with the Orvalho Geotrail and the International Appalachian Trail, two of the most popular hiking trails within the Geopark. These trails are the focus of the project for the new Interpretative Centre of the Orvalho village, where these and other fossils found along the trails will be exhibited and interpreted under the important geodynamic, climate, oceanographic, ecological and evolutionary changes that happened during the Ordovician Period. The environmental education Centre and the interpreted trails will be the scientific support of the educational programs already offered by the Geopark. The same can happen in Vila Velha de Ródão and Penha Garcia synclines. Fossil sites from Brejo Fundeiro, Fonte da Horta and Cabril formations at Portas de Ródão are protected under the national law for nature conservation, some of them included in the Master Plan of the municipality of Vila Velha de Ródão. The main road that crosses the Monument also intersects the entire Ordovician succession cropping out in this Variscan structure and has been successfully used for training university students in geosciences. Finally, the fossil sites of Ribeira do Reca and Fonte do Cuco, in the Penha Garcia Syncline, are geosites under the Geopark list; these and the other fossil sites, including the Vale Feitoso Estate, are located close to Penha Garcia Ichnological Park, the most important geotourism destination at Naturtejo Geopark. Also, an important Interpretative Centre of the Ordovician Paleobiodiversity is under construction and the studied fossils will be included and showcased from a paleoecological perspective in the permanent exhibition.

The trilobite-dominated, high paleolatitude marine assemblages from the Middle Ordovician, whose recent works increased the number of known species from 20 to over 40 in the Oretanian/Dobrotivian of Naturtejo Geopark area, including the first report of several genera (the trilobites Selenopeltis, Eccoptochile, Ogyginus, Asaphellus, Kerfornella, the bivalve Cardiolaria, the ostracod Quadritia, the rostroconch Tolmochovia, among others), reveal higher biodiversity than previously documented. This fossil record is representative of the High Latitude peri-Gondwana Realm for this period of time and, therefore, must be deeply analyzed at a regional level under the Global Ordovician Biodiversification Event and introduced to schools and public, through effective exhibitions and school programs, as one of the main examples of animal evolutionary radiation in the Phanerozoic.

Acknowledgments

The ongoing fieldwork is partially supported by Naturtejo, EIM under its program Geopark Science for Development. The authors also express their gratitude to the Municipality of Oleiros (Paulo Urbano) and the authorities of the village of Orvalho (Luis Roque) for their support; to Herdade de Vale Feitoso for the permit to work in this private property; to Ana Medeiros and Frederico Ferreira for helping in fieldwork at Vila Velha de Ródão and giving specimens for study; to Ana Jacinto and Francisco Piçarra for helping in fieldwork at Oleiros municipality, and Tim Young (Cardiff University) for sharing his data and knowledge. We thank Helena Couto (Universidade do Porto) and an anonymous reviewer for manuscript revision. This work was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia under the UID/Multi00073/2019 Project framework, Portugal.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare to have no conflict of interest