Introduction

The Geopark Bohemian Paradise is situated in the northern part of the Czech Republic, formerly Bohemia (Fig. 1). It is extraordinarily rich in various geological and paleontological features. The eastern part of the area is covered by upper Paleozoic deposits of the Krkonoše Piedmont Basin that are historically well known for their rich fossil record. One of the most interesting phenomena is petrified stems. Their frequency and esthetic value have always attracted the attention of local and foreign researchers (e.g., Březinová 1970). They were first described more than 150 years ago (Goeppert 1857, 1858; Renger 1858), and rarely superficially mentioned in the next decades (e.g., Feistmantel 1873 a, b, c; Feistmantel 1883; Frič 1912). However, they have never been studied in detail. Only in the last few years have they been studied intensively by researchers from the Geopark Bohemian Paradise in cooperation with the Charles University in Prague, Czech Geological Survey, and Czech Academy of Science, as well as colleagues from institutes abroad, e.g., Chemnitz Museum of Natural History, IRD/AMAP Institute Montpellier (e.g., Matysová et al. 2008; Mencl et al. 2009; Sakala et al. 2009; Matysová et al. 2010; Mencl et al. 2013a, b).

The result of a long and rich geological history of the Geopark area are many geological sites attractive for visitors. However, the petrified stems are not widely known and are often ignored. Based on modern research and new data, we can demonstrate the attractive geological history of the area much better.

The informal center of petrified tree trunk research is the town of Nová Paka, the “Eastern Gate to the UNESCO Geopark Bohemian Paradise”. It is situated in the heart of the Krkonoše Piedmont Basin and there are many places to find petrified stems around it. The most famous fossil site is probably Nová Paka - Balka, where petrified trunks were historically found. Currently, a large collection of about 2500 petrified stems is in the Municipal Museum in Nová Paka, and more than 600 specimens are presented in its exhibition, which is the largest in the Czech Republic.

Except for the Bohemian Paradise Geopark, late Paleozoic petrified stems are quite common in deposits of several coeval basins in the Czech Republic. The Krkonoše Piedmont Basin, however, shows the most complete fossil record (Mencl et al. 2009; Sakala et al. 2009; Bureš 2011; Mencl et al. 2013a, b; Opluštil et al. 2013). In Europe, stems of similar age are known from e.g., Sachsen, Germany and Autun, France (e.g., Rößler 2001; Rößler & Noll 2006; 2010, Rößler et al. 2012; Trümper et al. 2018).

Geological Setting

The Bohemian Massif, the easternmost part of the Variscan orogeny, was formed as a result of the closure of Rheic oceanic basins between Gondwana and Laurussia, and the collision of both continents at the end of Paleozoic (Dallmeyer et al. 1995; Žák et al. 2014). Faulting related to collision and Gondwanan rotation formed dozens of continental basins, with significant deposition since early Westphalian (e.g., Matte 1986, 2001; Pešek et al. 2001), which was several times interrupted by tectonic activity (Schulmann et al. 2014).

The late Paleozoic Krkonoše Piedmont Basin, which covers the eastern part of the UNESCO Global Geopark Bohemian Paradise (Fig. 1), represents the widest stratigraphic range among all others coeval basins in the entire Bohemian Massif. Purely continental deposits in the basin are Moscovian to Triassic in age, and their maximum thickness is about 1800 m. It is mostly composed of fluvial and lacustrine siltstones, sandstones and conglomerates, with sporadic content of volcanics (Pešek et al. 2001). According to the sedimentary and fossil record, the climate during the Pennsylvanian (Late Carboniferous) and Cisuralian (Early Permian) oscillated between wet and dry periods, and generally shifted from humid to arid (Opluštil et al. 2013).

Figure 1. Geographic position of the UNESCO Global Geopark Bohemian Paradise in Central Europe and its schematic geological map with sites.

The stratigraphic succession of the basin contains a very rich fossil record. Among researchers and private collectors, it is widely known for the presence of impressions of various flora, insects, fish, and amphibians, as well as ichnofossils. Moreover, there is also a well-known and rich occurrence of petrified stems, so-called silicified wood. In the past, these fossils were generally considered to be Early Permian (e.g., Feistmantel 1873a, b, c), but according to current research they cover a wider stratigraphic range, from Kasimovian to Sakmarian, and they occur in at least four stratigraphic levels (Pešek et al. 2001; Mencl et al. 2009; Mencl et al. 2013a, b; Opluštil et al. 2013; Fig. 2). They are most abundant in the so-called Ploužnice Horizon, which is part of the Semily Formation and is placed today very close to the Carboniferous / Permian boundary (Opluštil et al. 2016).

Figure 2. Stratigraphy of the Krkonoše Piedmont Basin with stratigraphic positions of petrified stems.

Petrified Stems of the Krkonoše Piedmont Basin

In this region, fragments of petrified tree trunks are most often found as loose pieces on hillsides, without any relations to the original deposits. They are less commonly preserved in outcrops, but always lying horizontally as allochthonous material, and never upright (Purkyně 1927; Mencl et al. 2009). They are usually preserved only as fragments of secondary xylem. Branches and bark with leaf scars are extremely rarely preserved (Renger 1858, 1863; Mencl et al. 2009, 2013b).

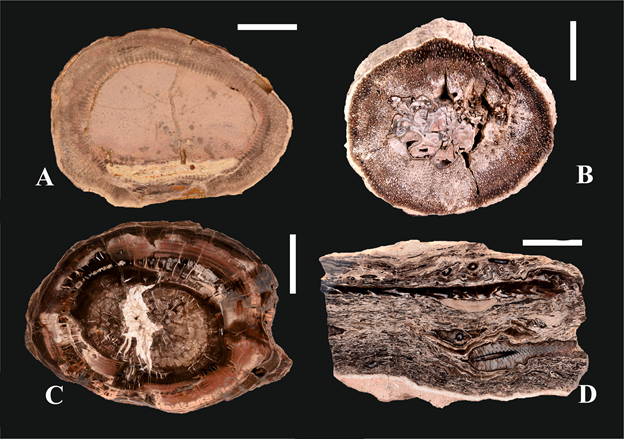

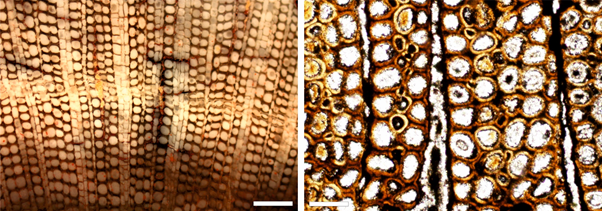

Based on present research and detailed anatomical studies of the plant tissues, various types of petrified plants were described in the basin, including arborescent calamitaleans and lycophytes, arborescent and climbing ferns, and gymnosperms as well (e.g., Mencl et al. 2009; Mencl et al. 2013; Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

Figure 3. A) Cross section of calamite Arthropitys bistriata, scale bar = 5 cm, B) Cross section of Psaronius tree fern stem, scale bar = 7 cm, C) Cross section of Agathoxylon sp. (conifer or cordaite), scale bar = 10 cm, D)Polished section of silicified peat with plant fragments as a lycopsid cone, scale bar = 5 cm. Courtesy of Museum Nová Paka, adopted from Mencl et al. 2013 (1) and Opluštil et al. 2013 (2, 4).

Arborescent calamitaleans of the Krkonoše Piedmont Basin can be attributed to two species: the common Arthropitys cf. bistriata and the rare Calamitea striata (Mencl et al. 2013a). In the area, calamitaleans of various sizes are found, from small axes a few centimeters in diameter, to big stems with diameters of almost 50 cm.

Most of the ferns are Psaronius sp., an arborescent marattialeans. The biggest specimen ever found in the Krkonoše Piedmont Basin is about 50 cms in diameter. Inside the root zone of their false stems are rarely found climbing axes of the fern Ankyropteris brongniartii, and small epiphytes of the fern Tubicaulis sp. (e.g., Frič 1912; Rößler 2000). The newest findings also prove the presence of Asterochlaena laxa, a small arborescent zygopterid fern (unpublished).

Figure 4. Detail of secondary xylem of arborescent calamite Arthopitys bistriata (left) and conifer Agathoxylon sp. (right). Scale bars = 0, 5 mm.

Stems of gymnosperms include two types: “seed ferns” (Medullosas) and stems of the genus Agathoxylon sp. of two types, cordaites and conifers (Mencl et al. 2013b). Medullosas are extremely rare in the basin. They are usually up to 20 cm in diameter and are currently studied intensively. On the contrary, stems of other gymnosperms are the most common and the largest among all petrified stems of the Krkonoše Piedmont Basin. They were described from four fossiliferous levels (mentioned above, Fig. 2). The biggest trunk, more than 8 m long and up to 1 m thick, was found in Nová Paka in 1953 (Fig. 5).

Other plant remains are known from large nodules, similar to coal-balls, preserved inside the fossiliferous deposits, and so-called “silicified peat”. This unique material presents the most complex view of floral assemblages of the area. It is composed of fragments of various plant tissues, including roots, small branches, reproductive organs, seeds, etc.

Figure 5. The biggest silicified stem excavated in Nová Paka in 1953.

Taphonomy and Interpretation

Most of the petrified stems and trunks are silicified, and only very few are calcified or sideritized. Except for the Ploužnice Horizon, the stems were silicified in alluvia without the apparent influence of volcanic material. The weathering of feldspars is assumed as a source of silicification amplified by oscillation of the water table under seasonally arid periods during the late Paleozoic (Matysová et al. 2010, Opluštil et al. 2013). Fine grained (lacustrine) deposits of the Ploužnice Horizon are intercalated with volcaniclastics (Pešek et al. 2001; Opluštil et al. 2016), which could facilitate excellent anatomical preservation (Matysová et al. 2010), and allowed other plants with tissues, which are not as resistant as secondary xylem, such as ferns and peat, to be preserved. Thanks to this, the floral assemblage of the Ploužnice Horizon represents the most complete fossil record in the basin. Based on the presence of wet-loving plants, the paleoenvironment and climatic conditions of the site and time span can be considered as rather humid and swampy (Mencl et al. 2013b). Unfortunately, no animal interactions with silicified stems have been found, despite the fact that various faunal impressions are very common in coeval stratigraphic units in the basin.

Geo-tourism and Geo-trail Potential

Economic Aspects

At present, the Municipal Museum of Nová Paka, which displays a valuable collection of fossilized plants, minerals and gemstones from the Bohemian Paradise (Fig. 6), is visited by nearly 15,000 visitors a year – since 2016 this number has gone up by 30%. It is expected that the activities of the Bohemian Paradise UNESCO Global Geopark will at least double this number in forthcoming years. The museum itself cannot achieve this goal without continuous institutional support from the town council of Nová Paka and the Ministry of Culture. The increase in the number of visitors will enable the museum to employ a part-time guide in the near future who, under the Petrified Forest Program, could offer an all-day experience to those visitors seriously interested in this subject. This would include a guided tour of carefully selected items from the collection of fossils, a multimedia presentation explaining the geological past (popular and often available for free or a small fee, and produced at top quality) and visits to sites within walking distance of the museum.

Figure 6.Exposition of Geological history and Petrified stems in Museum Nová Paka.

At present, the Czech-Polish cross-border project BALKA has been launched in Nová Paka which, among others, includes the establishment of an outdoor geological exhibition and educational trail around sites of geological interest. This project will help to increase the attractiveness of the region and will have a positive economic impact, especially on the hospitality sector.

Geo-tourism Effects on Life and Culture of Local People

The local government and the Nová Paka Municipal Museum, in cooperation with the Bohemian Paradise UNESCO Global Geopark, place a great emphasis on the promotion of local geological riches. In 2019, an application was submitted for expansion of the UNESCO Global Geopark territory to include geological sites around Nová Paka, mainly those to the east. Not only visitors but also local people who were fond of spiritualism in the past will benefit from the increased range of tourist attractions. However, it is of utmost importance to ensure that increased interest in the petrified wood does not result in looting of local sites by visitors or locals who collect these fossils on their land and often display them there. This should be prevented primarily through targeted education.

Education and Public Awareness

School education in the Czech Republic deals with Earth sciences quite briefly, usually in the context of natural science in year nine of the Czech basic school system. (Many children, however, leave the basic schools at year five for eight-year grammar schools.) In this context, it could be considered as a moral duty of headmasters of the schools situated in and around the Geopark to offer their pupils specialized lectures by Geopark experts or staff from cooperating professional institutions. The geologist from the Nová Paka Municipal Museum offers guided tours of the Museum, organizes geological excursions for schools, traditional Stonemason Days in the Museum and geological summer camps for children and young people.

The network of museums on the territory of the Geopark is adequate and well above the average, a result of several favorable circumstances: the tradition of hiking and spa treatments, the importance of the Bohemian Paradise in the Czech National Revival in the 19th century and numerous historical, cultural and natural heritage sites in the area. Each of the museums has its specifics and strengths (in Nová Paka it is the Petrified Forest, in Turnov minerals, etc.). The main goal to be achieved in terms of visitors is to make them perceive every specialized collection as part of a bigger collection from the Bohemian Paradise UNESCO Global Geopark and plan their visit to the region accordingly.

There was never a big deep mine within the boundaries of the Geopark, including the Krkonoše Piedmont Basin. The existence of a deep mine usually helps to keep awareness of the region's geological past for generations among the locals. It was relatively common that active mines organized public exhibitions (at least occasionally) of minerals, fossils and rocks; one of them has been preserved in the Jan Šverma mine in the neighboring coeval Intra-Sudetic Basin, some 35 km beyond the boundaries of the Geopark. The Geopark strategy could also contemplate synergistic co-operation with this organization or at least exchange references and recommend visits of each other.

Conserving Geo-sites: Actions, Solutions and Limitations (in past and future)

Government and Local Authority Approach and Policy

We believe that the Ministry of the Environment, the Ministry of Regional Development, the regional councils, town councils and local councils representing communities in the Geopark are aware of the fact that the operation of the Geopark requires regular funding and that any failure to do so could degrade many years of hard work. It is, therefore, crucial to provide statistical data on the number of visitors to the sites of the Bohemian Paradise Geopark so that municipalities, regional administrations and ministries can have a realistic idea about the return on their investment in the Geopark. We estimate that the Geopark will be comfortably financially solvent in a ten-year time horizon on the assumption that the global tourism concept which has worked well so far will not have to be abandoned.

The Role of Organizations in Conservation and Government Decision Making

The UNESCO brand itself guarantees extra interest in specific destinations and sites. It is primarily the task of the management of the Bohemian Paradise Geopark to sell this brand to the public as much as possible (trail signs, leaflets and national PR). However, for the promotion of the Bohemian Paradise UNESCO Global Geopark abroad, the active support of the Global Geopark Network’s elected and appointed representatives is necessary, though it must be we who offer the key promotional materials, articles on attractions, etc.

Suggestions and Perspectives

Late Paleozoic petrified trees of the Bohemian Paradise are one of the "cornerstones" of the Bohemian Paradise UNESCO Global Geopark. Publicly exhibited finds are already of an excellent standard and popular among occasional and regular visitors to the Geopark area. It is obvious that the petrified forest phenomenon has great potential to be linked with other geological and cultural sites in the region. The Bohemian Paradise Geopark and all its remarkable sites provide ample opportunities for better understanding and promotion of this unique area both nationally and internationally.

Conclusion

The rich fossil record in the area of the Geopark is very suitable for educational and training activities. New research on petrified wood allows us to make this phenomenon more attractive for visitors to the Geopark. Thanks to the results of other ongoing research on fossil faunas, volcanic processes and paleoenvironments, we can reconstruct an image of the area during the late Paleozoic (Fig. 7). Currently, there are several public exhibitions in museums and educational trails in the field. In the near future, a new interpretation center of the Geopark and educational trail, mostly focused on the local Carboniferous Petrified Forest, will be created at the Balka site at Nová Paka. These activities definitely increase the value and attractiveness of the Bohemian Paradise UNESCO Global Geopark.

References

Březinová D (1970). Přehled dosavadních nálezů fosilních dřev na území Československa zpracovaných na základě literárních pramenů. Manuscript. National Museum Prague.

Bureš J (2011). Zkřemenělé kordaity a konifery v sedimentech líňského souvrství plzeňské karbonské pánve. Erica. 18: 179–198.

Dallmeyer RD, Franke W, Weber K (Eds.) (1995). Pre-Permian Geology of Central and

Eastern Europe. Springer, Berlin.

Feistmantel K (1883). Über Araucarioxylon in der Steinkohlenablagerung von Mittel-Böhmen. Abh. d. k. b. Ges. d. Wiss. 6 (12): 1 - 24.

Feistmantel O (1873a). O zkřemenělých kmenech v permském útvaru českém. Vesmír. 2: 176-178, 190 - 192, 208.

Feistmantel O (1873b). Über die Verbreitung und geologische Stellung der verkieselten Araucariten - Stämme in Böhmen. Sitzungsberichte d. k. b. Ges. d. Wiss. 5: 204 - 220.

Feistmantel O (1873c). Geologische Stellung und Verbreitung der Verkieselten Hölzer in Böhmen. Verhandlung der k.k. geologische Reichsanstalt. 168 (6): 108 - 112.

Frič A (1912). Studie v oboru českého útvaru permského. Arch. přírodov. prozk. země čes. 15.

Goeppert HR (1857). Über den versteinerten Wald von Radowenz bei Adersbach in Böhmen und über den Versteinungsprocess überhaupt. Jahrbuch k. k. geologische Reichanstalt. 8: 725-738.

Goeppert HR (1858). Ueber die versteinten Wälder im nördlichen Böhmen und in Schlesien. Jahres-bericht der Schlesischen Gesellschaft für Vaterländische Cultur. 36: 41–49.

Matte P (1986). Tectonics and plate tectonics model for the Variscan belt of Europe. Tectonophysics. 126: 329–374.

Matte P (2001). The Variscan collage and orogeny (480–290 Ma) and the tectonic definition

of the Armorica microplate: a review. Terra Nova. 13: 122–128.

Matysová P, Leichmann J, Grygar T, Rössler R (2008). Cathodoluminescence of silicified trunks from the Permo-Carboniferous basins in eastern Bohemia, Czech Republic. European Journal of Mineralogy. 20: 217–231.

Matysová P, Rössler R, Götz, J, Leichmann J, Forbe G, Taylor EL, Sakala J, Grygar T (2010). Alluvial and volcanic pathways to silicified plant stems (Upper Carboniferous-Triassic) and their taphonomic and palaeoenvironmental meaning. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 292: 127–143.

Mencl V, Matysová P, Sakala J (2009). Silicified wood from the Czech part of the Intra Sudetic Basin (Late Pennsylvanian, Bohemian Massif, Czech Republic): systematics, silicification and palaeoenvironment. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 252: 269–288.

Mencl V, Holeček J, Roessler R, Sakala J (2013a). First anatomical description of silicified calamitalean stems from the Upper Carboniferous of the Bohemian Massif (Nová Paka and Rakovník areas, Czech Republic). Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 197: 70–77.

Mencl V, Bureš J, Sakala J (2013b). Summary of occurrence and taxonomy of silicified Agathoxylon-type of wood in late Paleozoic basins of the Czech Republic. Folia Musei rerum naturalium Bohemiae occidentalis. Geologica et Paleobiologica. 47: 1–2, 14–26.

Opluštil S, Šimůnek Z, Zajíc J, Mencl V (2013). Climatic and biotic changes around the Carboniferous/Permian boundary recorded in the continental basins of the Czech Republic. International Journal of Coal Geology. 119: 114–151.

Opluštil S, Schmitz M, Kachlík V, Štamberg S (2016). Re-assessment of lithostratigraphy, biostratigraphy, and volcanic activity of the Late Paleozoic Intra-Sudetic, Krkonoše-Piedmont and Mnichovo Hradiště basins (Czech Republic) based on new U-Pb CA-ID-TIMS ages. Bulletin of Geosciences. 91: 399–432.

Pešek J, Holub V, Jaroš J, Malý L, Martínek K, Prouza V, Spudil J, Tásler R (2001). Geologie a ložiska svrchnopaleozoických limnických pánví České republiky. Český geologický ústav, Prague.

Purkyně C (1927). O nalezištích zkřemenělých kmenů araukaritových v Čechách, zvláště v Podkrkonoší. Časopis Národního Muzea. 51: 113 - 131.

Renger K (1858). Skamenělé kmeny v Čechách. Živa. VI: 254.

Renger K (1863). O skamenělém lese radvanickém blíže Abrspachu a o spůsobech skamenění vůbec. Živa. 4: 362 - 375.

Rößler R (2000). The late Palaeozoic tree fern Psaronius – an ecosystem unto itself. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 108: 55–74.

Rößler R (2001). The Petrified Forest of Chemnitz. Museum für Naturkunde Chemnitz.

Rößler R & Noll R (2006). Sphenopsids of the Permian (I): the largest known anatomically preserved calamite, an exceptional find from the petrified forest of Chemnitz, Germany. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 140: 145–162.

Rößler R & Noll R (2010). Anatomy and branching of Arthropitys bistriata (Cotta) Göppert - new observations from the Permian petrified forest of Chemnitz, Germany. International Journal of Coal Geology. 83: 103–124.

Rößler R, Zierold T, Feng Z, Kretzschmar R., Merbitz M., Annacker V., Schneider JW (2012). A snapshot of an early Permian ecosystem preserved by explosive volcanism: new results from the Chemnitz Petrified Forest, Germany. Palaios. 27: 814–834.

Sakala J, Mencl V, Matysová P (2009). Nové poznatky o svrchně karbonských prokřemenělých stoncích stromovitých přesliček z Novopacka. Zprávy o geologických výzkumech v roce 2008. 111–113.

Schulmann K, Martínez Catalán JR, Lardeaux J M, Janoušek V, Oggiano G (2014). The Variscan orogeny: extent, timescale and the formation of the European crust. Geological Society of London, Special Publications 405:1–6.

Trümper S, Rößler R, Götze J (2018). Deciphering Silicification Pathways of Fossil Forests: Case Studies from the Late Paleozoic of Central Europe.Minerals 2018. 8(10): 432.

Žák J, Verner K, Janoušek V, Holub FV, Kachlík V, Finger F, Hajná J, Tomek F, Vondrovic L, Trubač J (2014). A plate-kinematic model for the assembly of the Bohemian Massif constrained by structural relationships around granitoid plutons. Geological Society of London, Special Publications 405:169–196.