The Nusplingen Plattenkalk and its Paleontological Background

At the beginning of the 19th century, the exploitation of pure Solnhofen-type platy limestones flourished because of their use in lithography, a method for reproducing large numbers of illustrations for books, maps or other printed forms. In the local kingdom of Wuerttemberg, which was relatively poor in mineral resources, geology and stratigraphy were recognized to be a prerequisite for the successful evaluation of potential natural resources. In 1837, Friedrich August Quenstedt (1809-1889) was employed as a professor at Tübingen University and started his studies of the Jurassic. One of his earliest students informed him about a small site close to the village of Nusplingen, where a local farmer had exploited Solnhofen-type limestones for floor tiles and similar purposes. Quenstedtʼs positive evaluation, published in 1843, resulted in several attempts at industrial exploitation of this Nusplingen Plattenkalk. However, most of the material did not have the quality required for lithography. During these efforts, a small limestone quarry was opened and interesting fossils were found, unknown from elsewhere in Swabia, but similar to those from Solnhofen in Bavaria: prawns and lobsters, cephalopods, sharks, coelacanths and other fishes, crocodilians and even pterosaurs. At that time, numerous amateur paleontologists sampled fossils from Nusplingen, and the material spread over Europe by exchange (e.g., Odin et al. 2019).

Since then, several attempts have been made to excavate this fossil site properly, first commercially by the fossil trader Bernhard Stürtz from Bonn and later by paleontologists and geologists from Tübingen University. These excavations focused on vertebrates. The results were unfortunately not very successful, because of insufficiently qualified personnel, rarity of the material as well as the lack of tools and skilled technicians for fossil extraction. It was often stated in the literature that the fossils from Nusplingen were of generally lower quality than those from Solnhofen and Eichstätt in Bavaria. As a consequence, this important site became almost forgotten.

Until the 1980s, the Nusplingen quarry was still accessible, but only the uppermost parts of the section were exposed and hence this quarry was rarely considered as a worthy destination for field trips. The situation changed completely when a team from the Stuttgart Natural History Museum evaluated the site, because the entire area had become protected and scientifically significant fossils were thought to be in danger. Despite many publications about the Nusplingen Plattenkalk and its fossils, fundamental questions concerning the age, paleoenvironment and genesis of this fossil Lagerstaette remained open. To answer these questions, the Stuttgart Natural History Museum started scientific excavations in 1993, which are still ongoing.

Location of the Nusplingen Plattenkalk Geosite

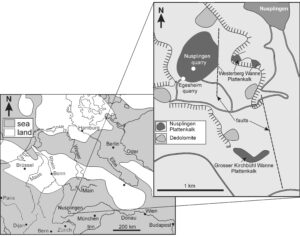

The Nusplingen Plattenkalk is well exposed in two small quarries exclusively dedicated to science, the Nusplingen quarry and the Egesheim quarry (Fig. 1), located ca. 250 m from each other on the ʻWesterbergʼ hill, west of the village of Nusplingen, atan altitude of c. 900 m above sea-level. The village and the geosite lie in the southwestern part of the Swabian Alb, within the area of the UNESCO Global Geopark Swabian Alb as well as in the Naturpark Obere Donau. The total thickness of the Plattenkalk section is 10–15 m, overlain by a few meters of brecciated olistoliths (Dietl et al. 1998; Bantel et al. 1999). Any younger Jurassic deposits have been completely eroded. The main outcrop area of the Nusplingen Plattenkalk covers less than 2.5 km2 and is mostly hidden in the subsurface of a meadow and forest landscape. A small relict occurrence of Plattenkalk crops out further to the south, along the southern foothill of the ʻGrosser Kirchbühlʼ hill. The latter site is important for reconstruction of the submarine relief during the deposition of the Plattenkalk. Siliceous sponge-microbial mounds had been tectonically uplifted and surrounded two 80–100 m deep lagoonal basins, named the ʻWesterberg-Wanneʼ and the ʻGrosser Kirchbühl-Wanneʼ (Dietl et al. 1998). Some of the uplifted mounds formed shallow islands in the Jurassic sea. Although these islands have been eroded, their former position can be reconstructed by mapping dedolomite occurrences. The Jurassic age of the formation of dedolomite was proved by dedolomitized lithoclasts occurring in breccia layers of turbidites within the Plattenkalk (Bantel et al. 1999).

Figure 1. Map showing the location and distribution of the Nusplingen Plattenkalk in the southwestern part of the Swabian Alb (modified from Klug et al. 2010a).

Nusplingen quarry (Fig. 2) can be reached by geological trails, either starting from the center of the village or from the parking lot on top of the hill, accessible by cars or small buses via a small signposted road (ca. 15 minutes by foot from there). It is accessible from early spring to late autumn, and even in winter if there is no high snow cover, although acces is then limited to times without snow, and excavations are impossible, because the limestones do not split when the ground is frozen. The Egesheim quarry, which is situated in a marginal position of the Nusplingen lagoon, is not accessible to the public, except during expert-guided field trips.

Significance of the Nusplingen Plattenkalk as a Geological Heritage

Nusplingen is one of a few sites of late Kimmeridgian age in the Upper Jurassic of southern Germany, several hundred thousand years older than the ʻclassicalʼ Solnhofen Lithographic Limestones in Franconia. In Swabia, however, it is the sole example of this type of fossil conservation Lagerstätten and one of the outstanding Jurassic geosites of the Geopark Swabian Alb. Despite the relatively small size of the outcrop area, the relatively rich and highly diverse fossil content makes Nusplingen a site of international reputation. Not only various groups of macrofossils, but also micro-, nano- and ichnofossils as well as excellently preserved terrestrial plants can be studied easily (e.g., Zügel et al. 1998; Bantel et al. 1999; Dietl & Schweigert 2004, 2011; Schweigert 2015), based on the rich fossil samples mainly housed in the collection of the Stuttgart Natural History Museum and from rock samples permanently accessible at the outcrop (hopefully also in future). All newly collected fossils and some of the historical specimens have been collected bed-by-bed thus allowing statistics on the abundance of taxa and the recognition of environmental changes through time. Most material from the ʻclassicalʼ Solnhofen Lithographic Limestones lacks such detailed information because of undocumented sources or deliberate misrepresentation by amateur collectors or fossil traders.

Figure 2. Scientific excavations of the Nusplingen Plattenkalk in the Nusplingen quarry. Photo. G. Schweigert.

The Nusplingen Plattenkalk is especially famous for well-preserved shark fossils (e.g., Fraas 1854; Schweizer 1964; Böttcher & Duffin 2000; Klug et al. 2009), namely the angel shark Pseudorhina acanthoderma (Fig. 3), of which 25 specimens have been recovered during excavations by the Stuttgart Natural History Museum, thus making this shark the iconic fossil of this geosite. Angel sharks from Nusplingen are not only on display in the Natural History Museum in Stuttgart, but also in the Natural History Museum of Vienna, in the Paleontological Museum of Tübingen University, and a few local museums. The shark fossils are preadult to adult males and females, whereas juveniles are missing; probably they grew up outside the Nusplingen lagoon. Further shark taxa inhabited the Nusplingen lagoon as well, as documented by complete specimens and isolated teeth (e.g., Notidanoides, Paraorthacodus, Synechodus, Sphenodus; Fig. 4). Marine thalattosuchian crocodiles (Cricosaurus, Dakosaurus) well adapted to marine life with their fin-like limbs and a tail fin resembling ichthyosaurs are identified as the top predators in the Nusplingen lagoon (De Andrade et al. 2010; Dietl & Schweigert 2011). The food web of this environment can be partly reconstructed by direct evidence such as stomach or crop contents and coprolites / regurgitalites of the involved animals (e.g., Schweigert & Dietl 2012; Hoffmann et al. 2019). Besides sharks, numerous other fishes have been recorded (e.g., Heimberg 1949; López-Arbarello et al. 2020; Maxwell et al. 2020). They often show some decay, but prepared from the bottom side, many of them are excellently preserved. A tiny isolated feather points to the existence of Archaeopteryx or similar theropods in the vicinity of the lagoon (Schweigert et al. 2010).

Figure 3. A male angel shark Pseudorhina acanthoderma (SMNS 96393/9) from the Nusplingen quarry found in 2013. Scale bar = 200 mm. Photo. G. Schweigert.

Figure 4. Skull of the shark Sphenodus nitidus (SMNS 96844/7) from the Nusplingen quarry. Scale bar = 50 mm. Photo: G. Schweigert.

Ammonites and their lower beaks (aptychi) are among the most common invertebrates of the Nusplingen Plattenkalk. In contrast to ordinary Upper Jurassic limestones, these ammonites were strongly compressed during early diagenesis; however, they sometimes include beaks and stomach contents still in the body chamber (Schweigert 1998b; Schweigert & Dietl 1999). Belemnite rostra and arm hooks are quite common as well; some belemnite animals show unusual preservation (e.g., Klug et al. 2010b). Isotopic data of belemnites and shark teeth have allowed for the reconstruction of paleotemperatures estimates for the living environment (Stevens et al. 2014; Hättig et al. 2019). Vampyromorph squids are preserved with ink, beaks and stomach contents (e.g., Klug et al. 2010a). Many benthic invertebrates (e.g., bivalves, brachiopods, echinoids, brittle stars, sponges) were accidentally brought in by predators. They often show evidence of predation such as bite marks or incomplete preservation, and many of them are represented by few or single records (e.g., Grawe-Baumeister et al. 2000; Scholz et al. 2008). Despite the dysoxic character of the seafloor, which prevented animal carcasses from being partly or completely consumed by scavengers, a few beds show low diversity endobenthic ichnofossil communities or interactions of animals with the sediment surface, like swimming trails of horseshoe crabs and mortichnia (traces of dying animals) of killed crustaceans and fishes (e.g., Schweigert 1998a; Briggs et al. 2005; Schweigert et al. 2016).

Some beds of the Nusplingen Lithographic Limestone are rich in kerogen, which is normally lost by oxidation. In these dark-colored bituminous beds, terrestrial plants, insects and other arthropods and even some ammonites are preserved with remains of organic matter (e.g., Schweigert & Dietl 1999; Dietl & Schweigert 2011). This is also the case for the large dragonfly Urogomphus nusplingensis (Fig. 5), an additional iconic fossil of this site (Bechly 1998). Among arthropods, decapod crustaceans are diverse, but only Antrimpos undenarius, a large prawn superficially similar to modern Penaeus, is frequently found in most parts of the section and preserved either as carcasses or as exuviae (Schweigert 2017).

Figure 5. Holotype of the dragonfly Urogomphus nusplingensis (SMNS 62602) from bituminous beds of the Nusplingen quarry. Scale bar = 50 mm. Photo: G. Schweigert.

In summary, with currently about 430 fossil taxa, the Nusplingen Plattenkalk site is among the most diverse Jurassic fossil localities worldwide in spite of the small outcrop extent. The seemingly much higher number of fossil taxa from the world-famous Solnhofen Lithographic Limestones of Bavaria results from a compilation of numerous sites of different ages and lithologies over a large area. Besides paleontological aspects, the Nusplingen Plattenkalk is one of the type localities for allodapic limestones (calcareous turbidites) – the other one is in the Carboniferous of the Rhenish Mountains (Meischner 1964). More details on the geology of the Nusplingen site and its fossils can be found in Dietl & Schweigert (2011) and Schweigert (2015).

Geotourism and Geoeducation

Geologists and paleontologists from nearly all continents have visited the Nusplingen Plattenkalk site. This is one of the outstanding sites within the Swabian Upper Jurassic regularly visited by teaching staff, students and participants of workshops, symposia or congresses in the fields of paleontology, geology, sedimentology, geochemistry, taphonomy and geotourism. For tourists visiting the Upper Danube area and other interested people, guided tours are offered by the ʻAlbguidesʼ of the Geopark Swabian Alb, the community of Nusplingen and the Naturpark Obere Donau. For those who prefer to visit without a guide, an elaborate geological trail ʻIns Reich der Meerengelʼ (= ‘entering the kingdom of angel sharks’) – also including local aspects of nature and historical land use – provides basic information on this geosite in the context of the Late Jurassic sea (Fig. 6). Since the village of Nusplingen is quite distant from the spectacular landscapes of the Upper Danube valley, the geosite of Nusplingen, together with the medieval church ʻAlte Friedhofskirche St. Peter und Paulʼ are important touristic attractions besides nature itself. From time to time, special exhibitions with newly recovered fossils are organized by the community of Nusplingen and the Stuttgart Natural History Museum, accompanied by popular lectures and expert-guided field trips. The outstanding paleontological importance of the Nusplingen lagoon means that the Nusplingen quarry has been a ʻgeopointʼ in the UNESCO Global Geopark Swabian Jura since 2018. Geopoints are important geosites in the geopark, where geology and geological history can be experienced by visitors.

Figure 6. The “main station” of the geological trail, located at the southern entrance to the Nusplingen quarry, provides information in Germany and English language. Photo: G. Schweigert.

Conserving the Nusplingen Geosite

The Nusplingen Plattenkalk is a specially protected site in the German federal state Baden-Württemberg, similar to the famous Lower Jurassic Posidonia Shale in the area of Holzmaden and the late Pleistocene travertines of Stuttgart. Originally, only the Nusplingen quarry itself was protected as a natural monument, when the ownership moved from Bernhard Stürtzʼs widow to the ʻVerein für vaterländische Naturkunde in Württembergʼ in 1938 (today: Gesellschaft für Naturkunde in Württemberg). After the illegal opening of a forestry quarry in 1980 (now Egesheim quarry), where scientifically important fossils became endangered, the entire estimated distribution area of the Nusplingen Plattenkalk became protected as a National Geological Heritage site on November 25th, 1983. After that time, excavating fossils has required special permission from the local government authorities, and this permission is restricted to scientific excavations. Even on the dumps of the quarries, search for common fossils without scientific significance (e.g., small ammonites, aptychi, small oysters) is only possible under the supervision of members of the excavation team during guided tours or on special events. Dump material from earlier years and open quarry walls provide rescue areas for rare plants, birds, reptiles and insects, thus increasing the local natural heritage aspects of the area in addition to the outstanding geological and paleontological values. Since there is no fence around the area of Nusplingen quarry, local people from the surrounding villages are instructed to observe this site during their daily walks. To prevent this scientifically most important site from illegitimate excavation or vandalism, another small quarry (originally opened for production of wall and floor tiles in the years after World War II) along the geological trail is open for enthusiastic young fossil collectors. They are allowed to look for common fossils or manganese dendrites there, but only with a small hammer and chisel (Fig. 7). Scientifically important fossils, which are not expected to be frequently found there, have to be presented to experts anyway, who will decide case by case whether such fossils are important or not.

Figure 7. Small public sampling site along the geological trail. Photo: G. Schweigert.

Suggestions and Perspectives

The Nusplingen Plattenkalk is an outstanding Upper Jurassic fossil Lagerstätte in the UNESCO Geopark Swabian Alb. Research is strictly coupled with scientific excavations, which make this site attractive both for scientific collaborators as well as geotourists in the Upper Danube area. To prevent collectors from illegally searching for fossils at the scientific quarry, the UNESCO Global Geopark Swabian Jura will set up a panel at the public fossil collection site, which will provide collectors information about the possible finds and geotope protection.

In the Stuttgart Natural History Museum, fossils from Nusplingen are exhibited in the Jurassic exhibition. A small permanent exhibition of fossils from Nusplingen in the village itself would strongly enhance the attractiveness of this geosite but is hardly realistic at this point. A possible solution could be to use already existing (geo-)touristic logistics in the area for permanent or temporary presentations, such as, e.g., the medieval church in Nusplingen or the Geopark information centers, like the splendid fossil museum ʻWerkforumʼ in Dotternhausen and the nature reserve center of the Naturpark Obere Donau in Beuron.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the volunteers and technicians of the Nusplingen excavation team, namely Gerd Dietl, Martin Kapitzke (both Stuttgart), August Ilg (Düsseldorf), and Burkhart Russ (Nusplingen), for their great enthusiasm over many years. Christian Klug (Zürich) and Kevin Stevens (Bochum) are thanked for their valuable suggestions on our draft.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.