Land Management Governance Model and Tourism in Australia

In understanding the environment in which community engagement can take place to foster geopark development in Australia, it is important to take account of the role of the three levels of government.

The national Australian Government markets tourism globally and is the principal point of contact with UNESCO. At the second level, there are eight State and Territory Governments responsible for all land use management (including mineral resources) and planning, including tourism development and marketing. At the third level, local government agencies (LGAs), are controlled by State Governments and provide most community services and tourism information through the auspices of local tourism organisations (LTOs).

The Kanawinka UNESCO Geopark Impasse

Whilst the concept of geotourism was first discussed in Australia in 1996 at an annual conference of the Geological Society of Australia. Australia’s first geopark, Kanawinka, was declared in 2008 after evolving from the development of a ‘Volcanoes Discovery Trail’ concept. This UNESCO approved geopark was formally announced in Australia at the Inaugural Global Geotourism Conference in Fremantle, Western Australia, in August 2008 (Dowling and Newsome 2008). The geopark (26,910 square kilometers in area) featured recent volcanism extending from the Naracoorte Caves in South Australia into the Portland (Victoria) shoreline and north as far as Penola and Mount Hamilton. (Fig. 1). It represented the sixth largest volcanic plain in the world with some 400 eruption points (Joyce 2010 and Turner 2013). The geopark was located across the two Australian states of Victoria and South Australia and was embraced by eight LGAs (Lewis 2010).

Figure 1. Kanawinka UNESCO Geopark, South Australia and Victoria

However, the Kanawinka Geopark was unable to gain State and Australian Government approval that would have enabled UNESCO to assign ‘global geopark’ status on an ongoing basis. This situation was reaffirmed when Australian Government Ministers for the Environment and Heritage Council (EPHC) met in November 2009. Noting that the cited ‘Resource Management Ministers’ are advised by Geological Survey agencies, this Council decided that ‘after consultation with Resource Management Ministers, whilst Australian governments support geological heritage, they had significant concerns with the application of the UNESCO Geoparks concept in Australia, especially without government endorsement. It was decided that existing mechanisms are considered sufficient to protect geoheritage in Australia.’

For reasons not made known publicly, ‘the Council requested that the Australian Government advise UNESCO that Australia would not recognize the Kanawinka Geopark because of the deficient UNESCO process in declaring it. Council also requested the Australian Government ask UNESCO to take no further action to recognize any future proposals for Australian members of the Global Geoparks Network, or to further progress Geoparks initiatives within Australia, including that for the Kanawinka Geopark, unless the formal agreement of the Australian Government has first been provided.’ In 2012, UNESCO had no other choice but to withdraw its Geopark designation for Kanawinka.

In recent years, the Kanawinka region has reverted to being developed as a series of linked geotrails with support provided by community groups and several of the LGAs, specifically the South Grampians Shire Council and the Mt Gambier City Council.

Overcoming Barriers to Geopark Development in Australia

In reflecting on the Kanawinka experience, back in 2008, and despite the lobbying efforts of the then Australian Geoparks Network, the concept of global geoparks was clearly not supported by government planning and tourism agencies; the concept did not fit at all well into the prevailing public land management arrangements administered by principally State/Territory Governments with full control of the use of ‘crown land’ for primary industry purposes and LGAs for control and zoning of private lands.

Moreover, the concept was also not embraced or understood by the geological professions, hence there was no constituency support that could be translated into political lobbying. Historically, the principal focus of geological activity supported by the professional societies has been directed at meeting the needs of the exploration and mining industries. However, a decade later, the pursuit of geotourism is now seen to offer the potential for new industries and employment opportunities through the development of major projects within Australia.

The Australian Geoscience Council Inc. (AGC) is the peak council of geoscientists in Australia. It represents eight major Australian geoscientific societies with a total membership of over 8,000 individuals comprising industry, government, and academic professionals in the fields of geology, geophysics, geochemistry, mineral and petroleum exploration, environmental geoscience, hydrogeology, geomorphology, and geological hazards. The AGC recognizes that the development of geotourism may be one of the best ways to communicate the value of geoscience to the broader Australian community. The AGC considers that this improved profile for geoscience is likely to have a positive impact in other areas of strategic importance, most notably the need for continuing tertiary enrolments in geoscience, which is required to meet Australia’s needs for highly qualified geoscience graduates and researchers into the future.

As far as the tourism industry was concerned, geotourism was simply written off as a ‘niche’ interest area for those visitors interested only in geology, rather than providing considerable content value to traditional nature-based tourism as well as cultural tourism, inclusive of indigenous tourism, thus completing the holistic embrace of ‘A’ (abiotic) plus ‘B’ (biotic) plus ‘C’ (culture) (Dowling 2013).

Even ecotourism (as part of the nature-based tourism mix) was still a relatively young history with then less than 20 years of development in Australia, as evidenced by the launch of a national ecotourism strategy in 1994. Moreover, ecotourism has developed over this period and to the present day with a focus on the biotic (flora and fauna) aspects of natural heritage, generally visited in protected areas such as national parks. Even today, ecotourism enthusiasts still see geotourism as ‘geological tourism’ and find difficulty in accepting the holistic embrace of the geotourism experience. This situation has not been helped by the fact that most rangers employed in Australian national parks have not been trained in geosciences.

In addition, State/Territory Government Geological Survey organisations were not supportive of geopark development and geotourism generally, with strongly expressed concerns about impact on access to land for exploration and mining, irrespective of UNESCO assurances that geopark development did not impact on these activities.

In fact, there are six Global Geoparks in Europe that are geoparks specifically because of their mining history, and that mining continues in some of these territories. For example, in the Marble Arch Caves Global Geopark (Ireland), there are many quarries – dolomite, limestone, a cement factory, and there is active exploration for shale gas, which would need to be extracted by fracking technologies. All these operations are undertaken in compliance with Irish legislation from both jurisdictions in the country. In Gea Norvegica Global Geopark (Norway) are located large larvakite quarries which export polished ornamental stone all over the world. In Magma Global Geopark (Norway) one of their partners is Titania A/S which operates as a mining company extracting ilmenite in Norway for the European titanium pigment industry.

It was soon realized that several significant steps needed to be undertaken to gain constituency support for geopark development within a framework of establishing geotourism as a new industry for Australia.

Geological Community Engagement: The Geological Society of Australia and the Australian Geoscience Council

Largely in response to the Kanawinka experience, but also in recognition of overseas developments in geotourism and geoparks, the Governing Council of the Geological Society of Australia (GSA) decided in 2011 to establish a formal Geotourism Sub Committee of its Geological Heritage Standing Committee. Later in 2014, Council established a separate Standing Committee focusing solely on geotourism, and over the following 12 months, arrangements were put in place to provide linkages with two other large professional societies with significant geological membership – the Australian Institute of Geoscientists (AIG) and The Australasian Institute of Mining & Metallurgy (AusIMM). The AusIMM subsequently provided strong support for the concept of geotourism and geoparks in its submission to the draft Australian Heritage Strategy of the Australian Government (AusIMM 2014).

Notably, one of the achievements of this initiating Geotourism Sub Committee was to obtain formal approval and adoption in Australia by the Governing Council of the GSA of a definition of geotourism. 'Geotourism is tourism which focuses on an area's geology and landscape as the basis for providing visitor engagement, learning and enjoyment'.

Moreover, the Geotourism Sub-Committee embarked on a campaign within the geological professional societies to promote the fact that geotourism is an emerging global phenomenon which fosters tourism based upon landscapes. It was explained that geotourism promotes tourism to ‘geo-sites’ and the conservation of geodiversity and an understanding of earth sciences through appreciation and learning, such learnings being achieved through visits to geological features, use of ‘geo-trails’ and viewpoints, guided tours, geo-activities, and patronage of geosite visitor centers. It was pointed out that ‘geotourists’ can comprise both independent travelers and group tourists, and that they may visit natural areas (including mining areas) or urban/built areas wherever there is a geological attraction (Robinson 2018).

In summary, the campaign emphasized that geotourism achieved the following outcomes.

- Celebrates geoheritage and promotes awareness of and better understanding of the geosciences.

- Adds considerable content value to traditional nature-based tourism which has generally focused only on a region’s biodiversity.

- Provides the means of increasing public access to geological information through a range of new digital technology applications.

- Contributes to regional development imperatives through increased tourist visitation, particularly from overseas.

- Creates professional and career development for geoscientists.

- Can provide a means of highlighting and promoting public interest in mining heritage.

- Celebrates geoheritage and promotes awareness of and better understanding of the geosciences.

- Adds considerable content value to traditional nature-based tourism as well as cultural tourism, inclusive of indigenous tourism.

The Governing Council also decided that the principal purpose of the newly formed Geotourism Standing Committee was to provide advice to the GSA about how best geotourism can be advanced and nurtured in Australia with the following terms of reference.

- Promote tourism to geosites and raises public awareness and appreciation of the geological heritage of Australia including landforms, geology and associated processes through quality presentation and interpretation.

- Provide advice to the Governing Council about how best geotourism can best be nurtured throughout all areas of Australia, including within, but not limited to, the declared Australia’s National Landscapes, World Heritage and National Heritage areas as well as within National Parks and reserves, urban environments, and mining heritage areas.

- Review and recommend strategies that offer the potential for active participation of governments, land managers, tourist bodies and GSA members in geotourism and related interpretation activities.

- Undertake conference/symposium and seminar activities directed at raising awareness of geotourism amongst Society members and others.

- Foster the publication of content which serves to raise awareness and appreciation of geotourism amongst governments, land managers, the tourism industry, the geological profession, and the Australian public.

As a further development, in 2016, the AGC decided to appoint the Chair of the Geotourism Standing Committee as its official expert spokesperson on geotourism.

Engagement with Government Geological Survey Organizations

During 2016, the Geotourism Standing Committee commenced a dialogue with the then Chief Government Geologists Committee (now known as the Geoscience Working Group - GWG), a body representing all the state and territory geological surveys as well as the national Geoscience Australia agency. This dialogue was focused on explaining the principles of geotourism and delivery mechanisms such as UNESCO Global Geoparks and geotrails. In July 2017, this body responded to the Standing Committee, noting the following operating trends in Australia relevant to geotourism development.

- The considerable interest in promoting geoheritage for public information and increased tourism revenue in regional Australia.

- The significant efforts by individual State/Territory Geological Surveys and Geoscience Australia in promoting geoheritage by publishing books, pamphlets, GIS-based apps, erecting explanatory signage, etc. describing sites and geotrails.

- Collaboration between State/Territory Geological Surveys, ‘parks and wildlife’ agencies, member-based geoscience organizations, tourism bodies, and LGAs or regional authorities in their jurisdictions to increase awareness of geo-and mining heritage generally and geoheritage sites, geotrails, and areas.

- Many geoheritage sites are contained within and protected by conservation reserves and some State/Territory Geological Surveys have established small geoheritage reserves to further protect important sites.

Engagement with Local Government/ Regional Development Agencies through SEGRA

Geotourism has been featured at annual conferences of ‘Sustainable Economic Growth Regional Australia’ (SEGRA) since 2012, events which engage with local communityand government agency leaders. The GSA Geotourism Standing Committee convened the inaugural geotourism workshop at the 2014 conference at Alice Springs in the Northern Territory. Geotourism workshopping continued as SEGRA 2015 held in Bathurst, New South Wales, an event which saw the genesis of the Etheridge and Warrumbungle UNESCO Global Geopark proposals. Geotourism workshops were also convened at SEGRA 2016 in Albany, Western Australia, SEGRA 2017 at Port Augusta in South Australia, at SEGRA 2018 in Mackay, North Queensland, and SEGRA 2019 in Barooga, New South Wales, with SEGRA 2021 convened in Kalgoorlie-Boulder, Western Australia.

At these events, the following benefits of geotourism development for communities in regional Australia have been explained.

- A mechanism for celebrating and raising awareness of mining heritage where applicable, both past and present.

- An opportunity to enhance community engagement and build value into ‘Social Licence’ considerations.

- By celebrating geological heritage, and in connection with all other aspects of the area’s natural and cultural heritage (and most significantly, Aboriginal heritage), geotourism enhances awareness and understanding of key issues facing society, such as using our Earth’s resources sustainably.

- By raising awareness of the importance of the area’s geological heritage in society today, geotourism gives local people a sense of pride, and strengthens their identification with their region.

In summary, it has been promoted to these conferences that the over-riding socio-economic benefits of geotourism are measurable economic outcomes through enhancement of traditional nature-based tourism - additional visitors, direct and regional economic output, household income and wages, and local (including Aboriginal) employment.

Engagement with the Tourism Industry through Ecotourism Australia Ltd (EA) and the Forum for Advancing Cultural and Ecotourism (FACET)

Progress has also been made in gaining support from the nature-based tourism operators. The peak nature-based tourism industry association - EA established in November 2013 a new industry grouping, the Geotourism Forum, to advocate and nurture the development and growth of geotourism recognizing that it is sustainable tourism with a primary focus on experiencing the earth’s geological features in a way that fosters environmental and cultural understanding, appreciation, and conservation, and is locally beneficial. The purpose of the Geotourism Forum was to advise EA of how best geotourism can be advanced and nurtured having regard to the EA’s interest in inspiring environmentally sustainable and culturally responsible tourism.

The Geotourism Forum co-convened a major geotourism workshop as part of the 2015 Global Eco Conference held at Rottnest Island, Western Australia; at the 2016 Global Eco Conference held in Hobart, Tasmania; in Adelaide, South Australia in 2017; in Cairns, Far North Queensland in 2019; and in Margaret River in Western Australia in 2020.

The West Australian based FACET has also been active in promoting geopark development over the past 15 years.

Engagement with the Australia’s National Landscapes Programme

The Geotourism Standing Committee has championed what was once known as the Australia’s National Landscapes (ANL) Programme because of the opportunity to promote geotourism concepts. The Programme was the first time the tourism sector, nature conservation managers and tourism advocacy organisations had worked closely together to present Australia’s top nature tourism experiences. The Programme facilitated coordinated tourism planning and management and provided a focus for international marketing. The Programme was delivered with coordinating bodies for each ANL made up of land managers, regional tourism bodies and local government. The system was ‘blind’ to land tenure boundaries and in that sense, resembled the geopark structure. Three of the ANLs straddled state borders, demonstrating a unique level of cooperative management. http://www.environment.gov.au/topics/national-parks/national-landscapes-0

The ANL Programme included the following regions: Australian Alps (New South Wales/Victoria), Australia’s Green Cauldron (New South Wales/SE Queensland border region), Great Barrier Reef and Wet Tropics area (Queensland), Australia’s Red Centre and Australia’s Timeless North (Northern Territory), Australia’s Coastal Wilderness (New South Wales/Victoria), the Flinders Ranges and Kangaroo Island (South Australia), the Great Ocean Road (Victoria), the Greater Blue Mountains and Sydney Harbour (New South Wales), the Kimberley, Ningaloo-Shark Bay and Great South West Edge (Western Australia), and Tasmania’s Island Heritage (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Australia’s National Landscapes

However, in 2014 the two key participating Australian Government agencies advised that they had stepped back from a central coordination role and would instead encourage local steering committees and the tourism industry, through the auspices of EA to further advance this concept. In 2017 the peak tourism industry lobby group (Tourism and Transport Forum Australia) released a white paper (TTF 2017) extolling the virtues of the ANL programme, a move that was considered to assist in promoting the development of geotourism.

Pre-Aspiring UNESCO Global Geopark Proposals in Australia

Pre-Aspiring UNESCO Global Geopark proposals were defined by the GSA Geotourism Standing Committee as those projects undergoing assessment to obtain community and government support prior to any application being lodged with UNESCO as an Aspiring UNESCO Global Geopark.

The process of developing a Pre-Aspiring UNESCO Global Geopark involved an ‘on ground’ assessment of the feasibility of any proposal brought forward by any grouping including government agencies. With compelling regional development imperatives in mind, two such proposals, the Etheridge region of Far North Queensland (some 40,000 square kilometres in area) embracing the entire Shire of Etheridge (Fig. 4); and the Warrumbungle region embracing three LGAs - Warrumbungle, Gilgandra, and Coonamble (Fig. 3) located in Northwest NSW (totaling some 27,000 square kilometers in area) have been subject to intensive assessment during 2017, following advice submitted to the Secretary General of the Australian National Commission of UNESCO advising that the ‘pre-aspiring’ nomination process had commenced. Progress achieved for these projects was reported to the 7th Global Geoparks Network Conference held in the United Kingdom in September 2016 and at the 5th Asia Pacific Geopark Network Symposium held in China in September 2017.

Figure 3. Warrumbungle Pre-Aspiring UNESCO Global Geopark area comprising the whole of Warrumbungle, Gilgandra, and Coonamble Shires, totalling some 27,000 square kilometers in area and inclusive of the Warrumbungle National Park, located adjacent to the township of Coonabarabran, North-West New South Wales

UNESCO Global Geoparks are ‘single, unified geographical areas where sites and landscapes of international geological significance are managed with a holistic concept of protection, education, and sustainable development (UNESCO 2021).

Even if an area has outstanding, world-famous geological heritage of outstanding universal value, UNESCO has determined that it cannot be a UNESCO Global Geopark unless the area also has a plan for the sustainable development of the people who live there. To succeed, a UNESCO Global Geopark nomination must have the support of local people (Brilha 2018).

By raising awareness of the importance of the area’s geological heritage in history and society today, UNESCO Global Geoparks provides local people with a sense of pride in their region and strengthens their identification with the area. The creation of innovative local enterprises, new jobs and high-quality training courses is stimulated as new sources of revenue are generated through geotourism, while the geological resources of the area are protected.

Of importance in the process is the realization that ‘while a UNESCO Global Geopark must demonstrate geological heritage of international significance, the purpose of a UNESCO Global Geopark is to explore, develop and celebrate the links between that geological heritage and all other aspects of the area's natural, cultural and intangible heritages.’ In this context, the first task of the proponent is to address the issue of geological heritage of ‘international significance’. In 2017, the Governing Council of the GSA assigned the Geotourism Standing Committee the role of assessing the international geological merit of the current (and any future) pre-aspiring UNESCO global geopark proposals, based on the advice provided by the appointed geoscience/mining heritage reference groups, provided that any assessments are to be endorsed by the Governing Council before they are made external.

Etheridge Pre-Aspiring UNESCO Global Geopark Proposal

For the Etheridge proposal, a highly knowledgeable Geoscience and Mineral Reference Group undertook a considerable amount of work in defining the international significance of this region located west of the Atherton Tablelands in Far North Queensland, identifying some 20 key geosites in addition to the existing tourism attractions of Undara and Cobbold Gorge as well as the Talaroo Hot Springs area managed by the Ewamian Aboriginal Corporation. In addition, the reference group developed a sophisticated GIS map of the region with smartphone connectivity, as well as excellent geological content for the proposed ‘Savannahlander’ rail geotrail. https://savannahlander.com.au/tour-home/

A heritage specialist also generated a fascinating overview of the mining heritage of the region.

Figure 4. Etheridge Pre-Aspiring UNESCO Global Geopark area comprising Etheridge Shire, Far North Queensland.

Ian Withnall, Chair of this reference group, produced the following general geological description of the proposed geopark (Robinson 2017). The Etheridge region’s geological history extends back 1700 million years when its oldest rocks were possibly deposited on the edge of a continent now forming the core of North America. They amalgamated with the Australian continent about 1600 million years ago during supercontinent assembly and were deformed and metamorphosed. After continental breakup, quiescence was punctuated by episodes of intense geological activity. The most violent resulted in vast outpourings of silica-rich magma in the Carboniferous–Permian. Fluviatile and marine sediments blanketed the region in the Jurassic–Cretaceous, but the older rocks were re-exhumed after Cenozoic uplift. Basaltic volcanism has occurred without major breaks for the last nine million years, and features lava tubes and very long lava flows. The region is potentially still volcanically active.

These events have contributed to a fascinating diversity of geology, mineral resources, and landscapes, which influenced the lives and customs of Aboriginal people and patterns of European settlement.

The assessment process included consultation with all key stakeholders (e.g., indigenous communities, national parks, tourism resorts) undertaking individual self- assessments; consultation with key State Government agencies; and community consultation including information bulletins, public meetings involving Shire Councillors.

The assessment identified the following natural and cultural assets.

- Geosites – In abundance with some 20 key geosites readily accessible to the public. Two geological events of Cainozoic age now feature as iconic geotourism attractions in the region, the most significant of which is the Undara Lava Tube cave system (Fig. 5), considered to be unique in the world based on consideration of age, preservation, and lineal extent, as well as the geomorphological expressions within flat-lying sediments at Cobbold Gorge (Fig. 6). Both landforms, as well as the other Proterozoic and Palaeozoic landforms in the area proposed for the Global Geopark, have resulted in a diverse range of landforms with special biodiversity characteristics including a rich assemblage of birdlife. (Withnall and Henderson 2012).

Figure 5. Undara Lava Tubes Figure 6. Cobbold Gorge

Latitude: 18° 12' 2.40" S 18° 47' 46.5" S

Longitude: 144° 35' 27.59" E 143° 25' 24.5" E

- ‘Geo villages’ – Four small townships, all with community engaged geosites (including agate, sapphire and gold fields); key established ecotourism resorts of Undara and Cobbold Gorge; and the indigenous Talaroo Hot Springs development, noting that the concept of a ‘geo village’ had been recently proposed (Martley 2016).

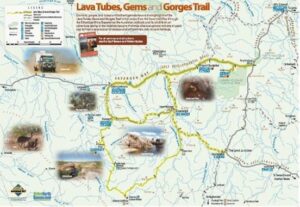

- Geotrails – The Lava Tubes, Gems and Gorges ‘Geotrail’, a 325 km transect of the Savannah Way (Figure 7) with connections to nearby mining heritage locations.

Figure 7. The Lava Tubes, Gems and Gorges ‘Geotrail’ of the Savannah Way: https://www.unearthetheridge.com.au/downloads/file/15/lava-tubes-gems-and-gorges-trail-map

- National Parks – Undara Volcanic Park and four other park areas.

- TerrEstrial Mineral/Fossil Museum– the most significant mineral museum in Queensland.

- Many heritage mining sites, and small gold mining operations underscores Etheridge’s status of one Australia’s most diversified mineralized areas.

The geological (and natural and cultural heritage) assessment proved the easy part of the process . A relatively short 12-month period allowed for the assessment and nomination completion process, a decision which did not provide sufficient time to gain full community support.

Whilst national park managers, indigenous groups, and residents of townships were very supportive, because they understand the economic benefits of tourism, agricultural and small-scale mining groups as well as gemstone fossickers were not supportive, with a vigorous program implemented to dissuade Council from finalizing the application. It was believed that the establishment of a Global Geopark upset the status quo. Issues raised were essentially fears of UNESCO control, more environmental regulation, and increased levels of tourism. The labels of ‘UNESCO’, ‘Geopark’, ‘Ecotourism’ etc. raised a range of concerns and fears.

Moreover, landholders, essentially graziers with long-term pastoral leases, feared that the proposed UNESCO affiliation would result in further regulation and restrictions curbing current and future activities and potentially leading to a World Heritage listing. Many considered that the large area of the application across the whole Shire which included large land tracts which were considered unlikely to be of interest for tourism. The use of the term ‘geopark’ was interpreted by many to imply some form of existing or potential environmental protection (aligned to an expanded, national parks network). There were also fears that the UNESCO branding would generate a response by the State Government to impose an additional layer of environmental protection, even though it was explained that UNESCO Global Geopark status does not imply restrictions on any economic activity within a UNESCO Global Geopark where that activity complies with indigenous, local, regional and/or national legislation. These fears were also shared by some elements of the mining industry involved in small scale mining operations.

Facing strong opposition, the proponent, the Etheridge Shire Council, decided not to proceed with the UNESCO Global Geopark application, and instead established a stakeholder Advisory Committee to advance geotourism using the natural and cultural assets that have so far been identified.

An Alternative Geotourism Development Strategy for the Etheridge ‘Scenic Area’

Etheridge Shire Council remained committed to developing tourism along with agriculture and mining as the three-fold basis of their forward regional development planning.

Council approved within the Shire of Etheridge, development of a major geotourism strategy which captures the aspirations of the pre-existing ‘Unearth Etheridge’ tourism strategy, providing additional natural and cultural heritage content; and through collaboration with other adjacent LGAs, establishment of strong geotrail linkages with geotourism attractions outside of the Shire. This alternative focused on developing an expansive principal focus on key geotourism areas within the Shire of Etheridge but to create linkages with key attractions outside the Shire utilising dedicated geotrails (Robinson 2017).

Emulating a program being undertaken in the United Kingdom, it was suggested that a ‘geo village’ approach (i.e., a community that has distinctive geology within its bounds, a policy of locally managed geological discovery and conservation, educational offerings for both schools and adults and that uses its geological assets in support of the local economy) could be considered for the Shire of Etheridge, thus enabling individual townships to take unique ownership of any activity e.g., community operated museum which has a natural or cultural heritage characteristic. Two of the small townships (Mt Surprise and Forsayth) have strong associations with agates and gems, and another (Einasleigh) has strong mining industry heritage. The main township, Georgetown, is the location of the TerrEstrial Centre mineral and fossil museum which might benefit from even a higher level of community involvement and the recently established Peace Monument has already made its mark. (Figs. 8 and 9).

Figure 8. Etheridge Shire Townships

Figure 9. TerrEstrial Museum and the Peace Monument, Georgetown

Warrumbungle Pre-Aspiring UNESCO Global Geopark

In New South Wales, the Warrumbungle proposal focused on the Warrumbungle National Park (Fig. 10) which is already included on Australia’s National Heritage List, a fact which would seemingly pre-qualify the area as being of international geological significance.

This heritage listed Park extends over a rugged mountainous area of sandstone plateaux and ridges and many prominent trachyte spires, domes, and bluffs (Fairley 1991). The 233 square kilometres of the park form part of the Warrumbungle Mountains, an eroded volcano of about 13-17 million years in age. In addition to its monumental scenery, the Park contains a varied complex of important plant and animal communities (Fairley 1991). In July 2016, the Park was the first within Australia to be certified as a Dark Sky Park by the International Dark Sky Association. https://www.darksky.org/our-work/conservation/idsp/

Figure 10. Warrumbungle National Park -view of the Breadknife and other peaks from Whitegum Lookout, looking southwest

The remainder of the Shire areas includes pastoral areas as well as native bushland such as parts of the iconic Pilliga Forest. In this instance, however, there was concern within the State Government that the establishment of any designation with some form of nominal ‘park’ status would result in land use conflicts with interests which are anti-development in nature. The Geological Survey of NSW (GSNSW) had strongly argued that the geopark be contained only within the Warrumbungle National Park. The Department of Planning and Environment had also flagged that they would like to see a comprehensive study undertaken to establish the economic benefits of the project to be weighed up with any political risk.

Although there was firm support emerging from the State Government tourism agency - Destination NSW, that a creation of a UNESCO Global Geopark need to substantially enhance tourism visitation to the region, at its meeting in April 2018, and after considering further the views of the GSNSW, the project Steering Committee decided to abandon plans to nominate for a UNESCO Global Geopark, and instead, accept the offer of the GSNSW to assist in developing an alternative geotourism strategy for the region that would include the establishment of a geotrail strategy e.g., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_V1oZeqdUg0].

Conclusions Relating to Local Community Engagement for Geopark Development in Australia

Lessons have been learnt from the experience gained from these two case studies. The following conclusions have been realized.

- More focus and time need to be applied to communicating the ‘geo-regional’ nature of geoparks. Whilst the promise of UNESCO branding offers the potential for economic benefit, it is a brand that can be seen mistakenly by landholders as conveying overseas control and more environmental regulation.

- More work is needed to overcome perceived fears about the detrimental impact of geoparks on other existing land users such as miners and other primary industry stakeholders.

- Geopark proposals must be supported by State Government Geological Survey organizations to the extent that these organizations are prepared to commit professional geological service when it is realized that geoparks can contribute to community outreach programs of government.

- Far more time must be allowed to gain community engagement/support to ensure geopark sustainability.

Agreed Key Factors for UNESCO Global Geopark Development in Australia

During 2018, the Geotourism Standing Committee came to understand that the following factors are essential requirements that need to be met to achieve Australian Government support for a UNESCO Global Geopark nomination.

- ‘Pre-Aspiring’ Geopark development needs to obtain state/local government agency endorsement and focused on a defined GeoRegion with outstanding geoheritage.

- A high level of community (including other land-user) engagement is essential to meet UNESCO requirements.

- The key driver of geopark development must be focused on regional development – i.e., jobs and growth and demonstrate economic benefit to offset perceived political risk.

- The approval of State/Territory Government Geological Surveys for individual projects is an absolute necessity, and it is hoped that the development of a national geotourism strategy might provide the mechanism for governments to evaluate major geotourism project proposals.

- Australian Government approval for UNESCO nomination may well be achieved if state/territory government endorsement and funding is clearly established.

Evolution of the National Geotourism Strategy (NGS)

As a response to the lessons learnt from the two case studies, the Geotourism Standing Committee commenced discussions with Geoscience Australia to consider a new process for assessing and seeking community and government support for UNESCO Global Geoparks development in Australia.

In November 2018, following discussions held at the AGC Conference in October and in pursuit of its inclusion as a Geoscience advocacy opportunity under the then AGC 2015-2020 Strategic Plan, the AGC established a coordinating role with the objective of developing a draft National Geotourism Strategy (NGS) under the umbrella of the AGC Advocacy Sub-committee. To accommodate the orderly development of major geotourism projects and activities in line with overseas trends and domestic regional development imperatives, the AGC saw the development of a national strategy, to be developed as a staged, incremental approach, as being essential to gain government endorsement at all levels.

It was envisaged that the NGS would support the economic benefit by:

- Leading to the establishment of a higher level of central coordination in areas of product development, travel and hospitality services, and tourism promotion, with a view to improving the overall visitor experience, consistency of the branding, and ultimately seeing an increase in visitor numbers.

- Maximization of sustainable development and management of ‘over tourism’.

- Establishment of a framework for focus on the 10 UNESCO Topics including culture, education, climate change, geoconservation etc.

- Maximization of community engagement.

The NGS was designed to support the orderly development of major geotourism projects and activities in line with overseas trends and domestic regional development imperatives.

The AGC saws the articulation of a strategy with a staged and incremental approach as being essential to ultimately gain government endorsement at all levels. The NGS also acknowledged the need to protect the scientific and cultural sensitivity of some geoheritage and geosites, and to ensure protection from geotourism where appropriate.

In 2020, the AGC set up a NGS Reference Group that included representatives of other key active stakeholders (e.g., the Geotourism Standing Committee of the GSA, The AusIMM, and the AIG), and under the guidance of this reference group, it was considered that other key stakeholder groups will be best placed to help deliver different parts of the NGS, which was launched in April 2021.

Seven key strategic goals are now being implemented by a series of working groups under the direction of a formalized AGC Steering Committee.

- Assessment and promotion of new digital technologies (e.g., delivered through smartphones and in visitor interpretation centers – 3D visualization, AR & VR) as a cost-effective means of accessing and better communicating and interpreting content for travelers.

- Consideration of establishing a national set of administrative procedures for ‘georegional’ assessment to provide, with government support, for potential geopark development at state and national levels, and as approved by the Australian Government, for nomination at a UNESCO Global Geopark level.

- Establish a framework for creating new geotrail development – local, regional, and national engagement to open dialogue with existing walking, biking, and rail trail interest groups and operators to highlight the availability of quality natural heritage information.

- Establish national criteria for geoheritage listings suitable for geotourism.

- Develop geotourism in regional mining communities with potential geoheritage and cultural heritage sites.

- Strengthen Australia’s international geoscience standing through geotourism excellence.

- Develop and enhance the geoscience interpretation and communication skills of everyone actively involved in the presentation of geosites, enabling the provision of accurate and thematic information in an accessible manner.

Two of the Strategic Goals embrace outcomes that will require engagement with communities.

- Goal 2 focuses on defining an approval pathway for major geotourism projects with two GeoRegion projects (Ku-ring-gai and Murchison) being included as project pilots.

- Goal 5 focuses on developing geotourism in regional mining communities with potential geoheritage and cultural heritage sites, where surfaces are exposed by mining, and their recreational, educational, and cultural values can be realized. Goal 5 also aims to draw attention to these places, and to the range of activities that could be conducted in these places. It is understood that the acknowledgement of Aboriginal cultural heritage beyond the benefits offered through geotourism includes the need to ensure it is appropriately protected. This will ensure the preservation of Aboriginal cultural heritage is equally as important as that of mining and other aspects of cultural landscapes, thus leading to improving the public perception of mining professionals and the industries in which they work.

Discussions between the AGC and the GWG have continued, particularly since the launch of the NGS, with the objective of determining the extent of government endorsement and engagement during its implementation process. The GWG has recently nominated one of its members to help formulate a new National Geoparks Committee, a grouping that is planned to emerge as an important outcome of the NGS implementation process, particularly involving the current working group No 2 charged with the job of determining an approval pathway for major geotourism projects.

In response, the AGC under the leadership of Dr. Jon Hronsky OAM, the Immediate Past Chairman of the AGC and a leader in minerals exploration in Australia, has now established a new Steering Committee to lead the overall implementation of the NGS. This Steering Committee comprises the Working Party Chairs as well as representatives of the resources, environmental sciences, and Aboriginal communities.

It has been agreed with GWG that the goal of the National Geoparks Committee is to ensure the development of a policy framework that ensures that any Aspiring UNESCO Global Geopark nomination is based on an identified GeoRegion that embraces geosites where sites and landscapes of international geological significance can be managed with a holistic concept of protection, education, and sustainable development. It is understood that a GWG member will have a key role on the new National Geoparks Committee and that technical advice can also be sought from respective jurisdictions on geological matters where appropriate.

It was also significant to note that Geoscience Australia (the Australian Government geoscience agency) joined with the AGC in June 2021 in making submissions in support of geotourism to an Australian Government inquiry focusing on ‘Reimagining the Visitor Economy. Moreover, the Geological Surveys of New South Wales, Western Australia and Tasmania have been proactive in encouraging the development of local and regional geotrail development.

Recommendation for Geopark Proponents in Australia

It has now been recommended that any geopark proponent should, in the early stages of project conceptualization, would adopt strategically a nomenclature which removes reference to the word ‘geopark’ and focus instead on communicating the concept of a ‘GeoRegion, a feasible strategy that addresses the local need in Australia.

This approach offers the opportunity for proponents within Australia using the language of ‘GeoRegions’ to explore various alternative options for geotourism development, including a strong focus on the establishment of geotrails between sites of geological merit as interpretive sites, including robust geoheritage sites, some of which may already have been established as geological ‘monuments’ or recognized in state or national geoheritage registers. From an UNESCO evaluation perspective, this approach also serves to establish a status of a ‘de facto’ geopark prior to any nomination for an Aspiring UNESCO Global Geopark being formulated.

Once a GeoRegion has been identified, then a full audit of natural and cultural heritage attributes in the region as well as early discussions with state/territory based Geological Surveys, planning and environment agencies, and any other state/territory government agencies responsible for land and resource management could be undertaken.

Two GeoRegion projects are now being developed as pilots under the auspices of the NGS with long-term aspirations of being supported by their respective State Governments of being nominated as Aspiring UNESCO Global Geoparks. In addition, in 2020 following the adoption of geotourism as the principal driver of their Destination Management Plan, Glen Innes Severn Council, located in the New England region of Northern New South Wales, is currently seeking the support of the GSNSW for the ‘Glen Innes Highlands’ to be recognized as a new GeoRegion. The Council considers this move as the starting point for formulating a nomination as an Aspiring UNESCO Global Geopark subject to State Government approval based on major geotourism developmental work and community consultation to be undertaken over the next few years.

Ku-ring-gai GeoRegion Project, Sydney, New South Wales

The Friends of Ku-ring-gai Environment Inc (FOKE), a community organization, has initiated a project with the objective of making a positive contribution to conservation based in and around Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park, located on the northern outskirts of Sydney (and within the area forming part of the former Sydney Harbour National Landscape), by seeking recognition of the very significant natural and cultural heritage values as exemplified by a wide range of geosites (Martyn J E 2020) which exist in this GeoRegion (Fig. 11). This is not unprecedented in New South Wales as other geosites and geotrails have similarly been recognized at Port Macquarie, Newcastle, Warrumbungle National Park, Central Darling River region and Mutawintji National Park.

Having conferred with a range of experts on the geology, geomorphology, and related natural and cultural heritage values of Ku-ring-Gai Chase National Park, it was decided to investigate further particularly the special geoheritage values which exist in the proximity to the Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park area. These geoheritage values (both geomorphological and geological) form the platform for the development of the other natural heritage attributes as well as demonstrating the close relationship between landscape and human activity over many thousands of years (Attenbrow 2010). The GSNSW has advised that, while concerned that appropriate steps will need to be taken by three LGAs and the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service to ensure that visitor impacts are properly managed, the Survey has no objection to any proposal to develop this GeoRegion embracing some 250 square kilometres in area as an Aspiring UNESCO Global Geopark.

Murchison GeoRegion Project, Western Australia

Inspired by participation in a SEGRA 2014 conference, Western Australia’s Mid-West Development Commission (MWDC) is working with seven LGAs to establish WA’s first major geotourism development to be built on a geotrail model, focused on the extensive Murchison GeoRegion of WA, located some 550 km north of Perth (Fig. 11). The MWDC believes that the ancient Murchison geology provides the ideal platform for unique, nature-based tourism experiences of global significance, particularly to the ‘experience seeker /dedicated discoverer’ market. The Mid West Tourism Development Strategy (2014) concluded that the region’s iconic nature-based tourist attractions were not developed to their potential and that its visitor appeal was not fully realized. The Strategy identified geotourism in the Murchison sub region as a potential ‘game changing’ tourism initiative, with capacity to help the region realize its potential as a major tourism destination, with the potential of being nominated as an Aspiring UNESCO Global Geopark.

Figure 11. Australian GeoRegions currently being assessed as potential Aspiring UNESCO Global Geoparks

Recognizing the outcomes of recent Ph.D. work focusing on stakeholder perceptions of establishing a geopark in Western Australia', completed in 2020 by Dr. Alan Briggs, President of Geoparks WA, Briggs et al. 2021) has recently published a paper 'Geoparks - learnings from Australia' which articulates some personal insights about future geopark development in Australia, but does not address the commitment of the AGC and the NGS directed at geopark development across all of Australia.

As a new way forward, the AGC remains confident that the implementation of the NGS will gain endorsement and support at all levels of government, given the success of such initiatives in other countries, resulting in considerable economic, employment and societal benefits, in particular for regional Australia.